With its turquoise waters and sunny skies, today the Caribbean is thought of primarily as a vacation destination. The Caribbean is integral to the idea of American wealth and almost always has been—not just as a leisure spot for those of means but in more nefarious ways as well.

A crucial leg of the Atlantic Slave Trade, also called the Triangular Trade, it was sugar colonies in the Caribbean that first brought captive Africans to the Western hemisphere. They harvested and processed sugar cane into white gold in brutal conditions.

The first Caribbean sugar plantations began in Barbados in the 1640s. This highly profitable and inhuman farming system became the prototype for the plantations elsewhere in the West Indies and in the American South. By the end of the 17th century, trade between European-Caribbean and European-North American colonies was brisk, with goods moving back and forth and across the seas to Europe and Africa, the latter in trade for human beings to keep the system going.

In addition to sugar, Caribbean plantations produced spices like nutmeg, cinnamon and pepper transplanted from the Eastern hemisphere. Native foods like pineapple, allspice and cocoa became precious commodities arriving to ports like Charleston, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston destined for the homes of the wealthy.

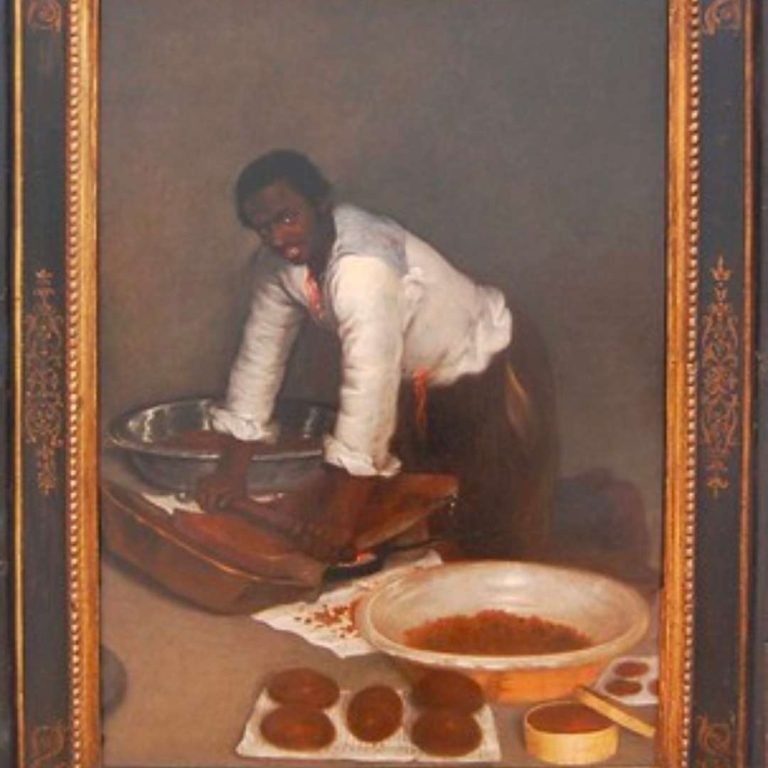

Cocoa became a must-have beverage at breakfast. Martha Washington was a fan while her husband, George, preferred a light tisane made from cocoa shells. In the most affluent homes, like Stratford Hall, the home of the Lees of Virginia, enslaved cooks ground chocolate using the same methods of the indigenous people of central America where Cacao originated. This stone called a matate was wide, and slightly cupped, resting on short legs and was heated. The cocoa beans were ground with a heavy stone that resembled a squat rolling pin.

I would take the liberty of requesting you’ll be so good as to procure and send me 2 or 3 bushels of the Chocolate Shells such as we frequently drink Chocolate of at Mt. Vernon, as my Wife thinks it agreed with her better than any other Breakfast.

– George Washington, 1794

By the early 1700s cocoa beans were being shipped to North American cities to be processed with spices into blocks for drinking chocolate and other uses. It may be surprising, for example, but chocolate cream pie, or chocolate tart was a common dessert in the 18th century.

The chocolate of this era was far different from what we know today—it was a grittier product and usually flavored with spices like nutmeg, cinnamon, and allspice in a recipe like traditional Central American and Mexican preparations. The smooth, creamy chocolate we know today was not available until later in the 19th century when machinery was invented to grind the pure cocoa paste more finely and add back cocoa butter and sugar during the refining process.

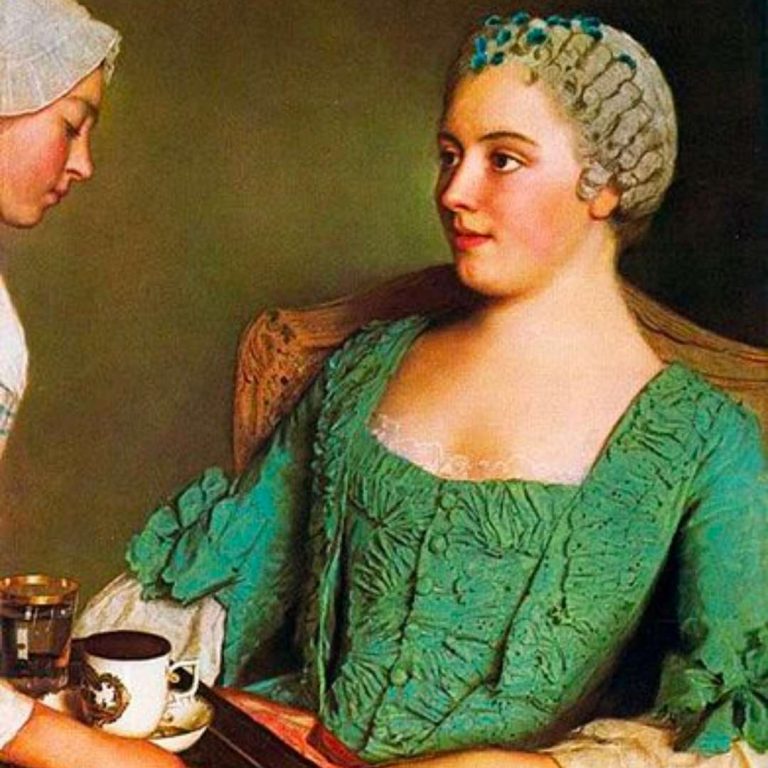

Despite not being the melt-in-your-mouth product, we know today, chocolate was trendy enough in the colonial period to warrant its own sense of accoutrements including chocolate preparing pots, serving pots and drinking services. These remained popular into the later 19th century. Some examples of finer cocoa pots included swizzle sticks to reagitate the chocolate that naturally sunk to the bottom of the vessel before serving.

Chocolate Tart recipes are quite common in cookbooks of the period such as Englishwoman Hannah Glasse’s 1747 book The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Modern readers might be surprised that Glasse’s recipe (and most others of the time) calls for rice flour which is used as a thickening agent. Rice and rice flour were commonly used since rice came to England and later America, via the robust British trade with the East and West Indies. Later, rice was grown in the southern American colonies as well. This recipe we share below uses cornstarch as a more effective thickener, however you can harken back to yore and substitute rice flour instead.

Traditionally this tart would have been served with a sugar crust on top like a crème brulee but we prefer to serve it with Chantilly cream (sweetened whip cream).

Chocolate Tart Recipe

Makes 1, nine-inch pie

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon cornstarch or rice flour

- ¼ cup sugar (or to taste)

- 4 large egg yolks

- 2 cups heavy cream

- 1 tablespoon whole milk

- 6 ounces semisweet chocolate chunks or chips

- Pinch of salt

- 1 9-inch pie shell, frozen or use our recipe here

Directions

- In a medium bowl, mix cornstarch or rice flour, sugar and egg yolks and set aside.

- Mix the cream and chocolate in a medium saucepan over medium heat and bring it to a boil, stirring constantly until the chocolate melts. Do not allow the mixture to boil.

- Add the milk and pinch of salt. Stir well.

- Using a ladle, pour 1/2 cup of the chocolate mixture in a very thin stream into the egg mixture, whisking vigorously the whole time. You may also do this in the bowl of a stand mixer.

- Add the egg and cream mixture back to the pot with the remaining chocolate cream mixture and whisk well. Heat over medium heat, whisking well until thickened, about 2 to 3 minutes. Remove from heat and allow to cool completely.

- Preheat the oven to 350F. If using homemade pie crust, line a 9-inch pie plate with rolled out crust. Pour the cooled chocolate mixture into the pie crust and bake until firm—about 40 to 45 minutes.

- Remove from oven and cool completely. Wrap in plastic and cool at least 8 hours but preferably overnight. Serve with Chantilly Cream.