Author: Michelle Shen

Third Annual Winter Market at Westport Museum for History & Culture

Westport Museum to Hold Multicultural Community Fellowship

Fighting for Freedom: Black Soldiers in the Civil War and Connecticut’s 29th Colored Regiment

Contributing Writer: Talia Moskowitz

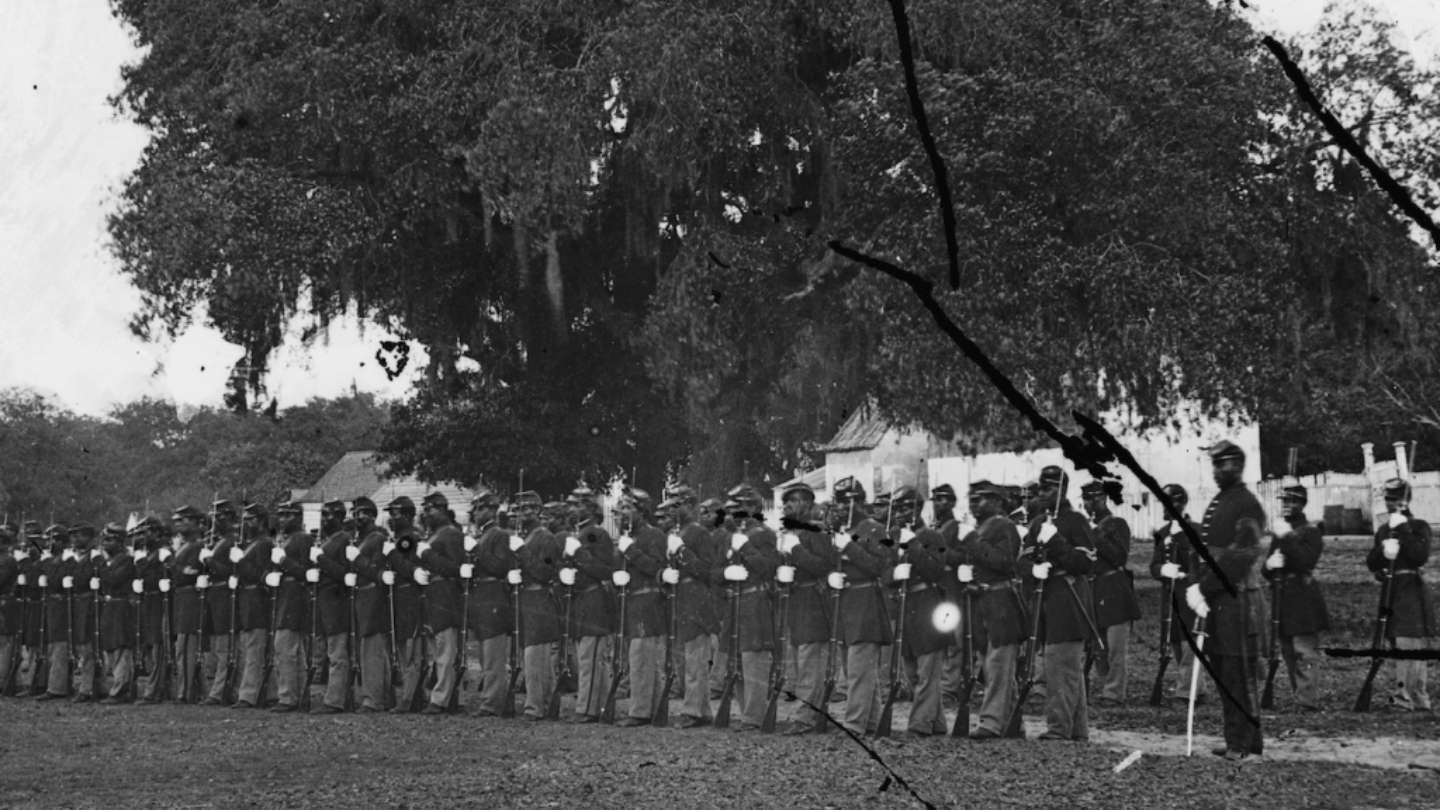

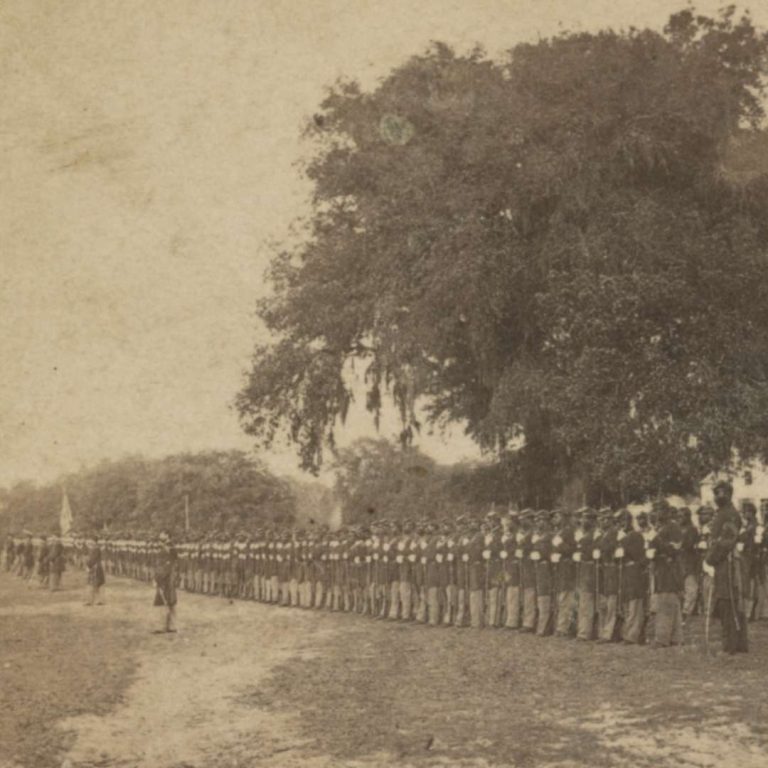

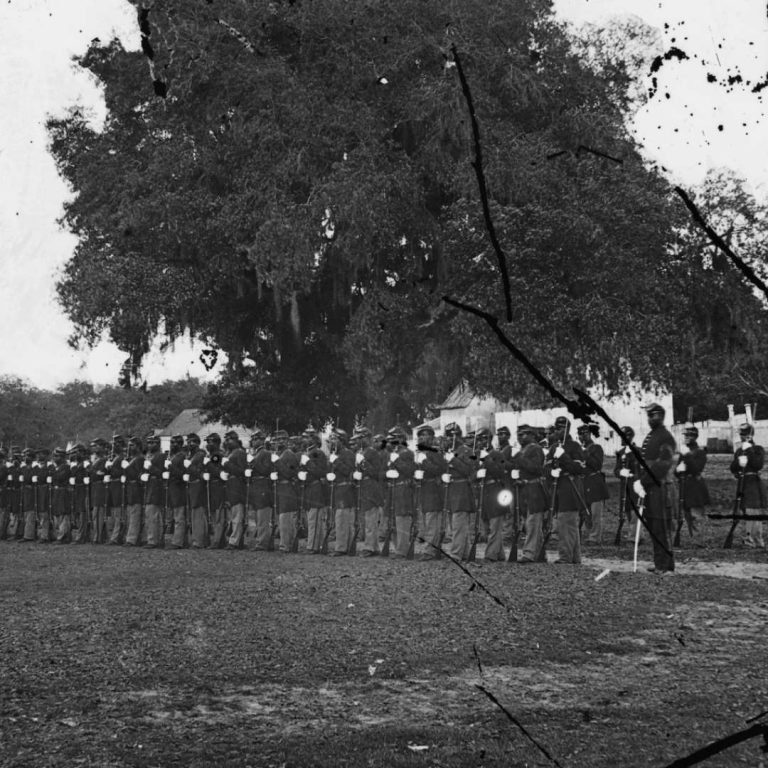

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed in January 1863, freed enslaved people in the rebelling Southern states and allowed for the enlistment of African American soldiers into the Union military. On May 22nd of the same year, the United States Department of War issued General Order No. 143 which established the Bureau of Colored Troops. On November 13th, 1863, Colonel Dexter R. Wright and Colonel Benjamin S. Pardee proposed a bill authorizing Connecticut Governor William A. Buckingham to organize regiments of “colored” infantry. Connecticut Democrats, including Westport’s representative John Wheeler, denounced the bill. They argued that it would unleash “a horde of African barbarians” onto the South. They believed that the North would lose if Black soldiers were allowed to fight, alleging that Black soldiers were cowardly and disgraceful.

Nonetheless, Governor Buckingham authorized the bill, calling volunteers to make up the 29th Regiment Colored Volunteers. The response from the community of color in Connecticut was immediate and enthusiastic. In 1860, according to the census, less than 1.2% of Westport’s population was Black. While Black men made up .4% of the Westport population—only 14 individuals—13 enlisted. The 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment was organized at Fair Haven, Connecticut, under the command of Colonel William B. Wooster and mustered into service on 8 March 8th, 1864. In a state where 1.8% of the population was Black, the 1,600 Black men who enlisted made up 94% of the African American community who were eligible to volunteer.

Photos of Connecticut’s 29th Regiment, taken in Beaufort, South Carolina, 1864. (Library of Congress)

By January 1864, more than 1,200 Black men volunteered to join the 29th regiment. 400 of those joined the overflow colored regiment, the 30th, in January 1864. The 30th was later folded into the 31st Colored Infantry Regiment, which was mustered into service April 29th, 1864, on Hart Island in New York City.

On January 29th, 1864, the soldiers of the 29th and 30th regiments listened to an address at the mouth of the Mill River in Fair Haven, Connecticut by the famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who told them:

You are pioneers of the liberty of your race. With the United States cap on your head, the United States eagle on your belt, the United States musket on your shoulder, not all the powers of darkness can prevent you from becoming American citizens. And not for yourselves alone are you marshaled—you are pioneers—on you depends the destiny of four millions of the colored race in this country. If you rise and flourish, we shall rise and flourish. If you win freedom and citizenship, we shall share your freedom and citizenship.

— Frederick Douglass, 1864

The 29th Regiment was present and took part in the last attacks against the Confederate capital city of Richmond, Virginia, in April 1865 and were among the first to triumphantly march through Richmond’s streets. The 29th Regiment continued to fight after the war was “over” and reported for duty in Texas alongside their Connecticut brethren in the 31st. They aided in the efforts to enforce the emancipation of enslaved people in Galveston and oversee the peaceful transition of power, heading to Texas on June 10th and remaining until they were ordered to muster out of service on October 14th, 1865.

There are fourteen members of the 29th Regiment listed as Westport residents. They are: Private (Pvt.) Samuel Benson, Pvt. Thomas Benson, Pvt. James Burns, Pvt. John Frye, Pvt. Thomas Gregory, Musician Frank Jackson, Pvt. Joseph H. Jackson, Pvt. William H. Jackson, Pvt. William H. Johnson (1st), Pvt. William H. Johnson (2nd), 1st Lieutenant Louis R. McDonough, Pvt. John Thompson, Pvt. Charles C. Williams, and Pvt. Charles Yan Tross. (Note: You may notice a discrepancy between our previous claim that 13 Black Westport residents enlisted, yet 14 names are listed here. That is because Louis R. McDonough was White.)

Visit Our Exhibit

Interested in learning more about the Civil War in Westport? Visit our student-curated exhibit, “Reluctant Liberators: Westport in the Civil War.” The exhibit is free to view in our programs gallery and on display until November 11th, 2023.

A Brief Glimpse into the History and Fashions of Gay Weddings

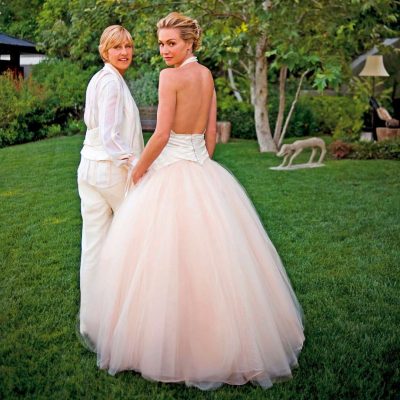

For centuries, people in the gay community were unable to legally marry their chosen same-sex partners. Connecticut set a precedent by becoming one of the first of the American states to legalize gay marriage in 2008, but the fight for marriage equality in the United States continued. In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized same-sex marriage as a matter of law. The result was a boom in formal marriage ceremonies among the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ+) community.

Choosing Their Own Path

Even before legal recognition, queer weddings were not new. Photographs and accounts of historic LGBTQ+ weddings were often carefully hidden away to ensure the safety of the couples and those in attendance. The few surviving photos provide intriguing glimpses into how LGBTQ+ couples chose to dress on their special day. While heterosexual tradition dictated that women wear gowns and men wear tuxedos, but no such formal precedent existed for LGBTQ+ couples.

Queer couples…began to transform gender roles surrounding marriage to fit their unique needs… With each wedding, couples continue to personalize the traditionally heteronormative fashions of marriage.

Many LGBTQ+ couples did not conform to traditional gender roles. Surviving photos show some LGBTQ+ couples opting for conventional, gender-normative wedding garb, while others selected outfits that flouted tradition.

Queer couples — especially those composed of two women — began to transform gender roles surrounding marriage to fit their unique needs, with some women wearing tuxedos while others donned traditional wedding gowns. With each wedding, couples continue to personalize the traditionally heteronormative fashions of marriage.

What the Photos Tell Us

Images that depict historical LGBTQ+ weddings can be seen on the internet. Unfortunately, we are unable to show most of them because they can’t be verifiably sourced. As a result, we are only able to describe these photos here. In one photo (circa 1930) showing the marriage of two women, one of the participants wears a wedding gown while the other wears a man’s military uniform complete with a sword. In three photos (circa 1928) of two women in wedding attire, one woman wears a white dress while the other sports a man’s suit and top hat.

Overall, there is a sad deficit in our knowledge about what LGBTQ+ couples wore when celebrating their weddings in decades and centuries prior. However, the photos and accounts that have survived give us some insight into the traditions and fashions of same-sex marriage. The trend continues today as modern couples celebrate their hard-won freedom to openly participate in an institution which historically denied them access.

Want to learn more about the history of wedding fashions? Visit our exhibit I Thee Wed: Bridal Fashion from the Collection to see some of the Museum’s stunning wedding gowns and learn their stories.

Learning the Language

- Heteronormativity is the assumption that heterosexuality – attraction to the opposite sex – is “normal” and “natural.” It assumes people are heterosexual by default and can be used to construe homosexuality – attraction to the same sex – as “unnatural.”

- LGBT is an initialism of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender. Sometimes a Q+ is added to include Queer and other sexual identities (LGBTQ+).

- Queer is an umbrella term used for those who do not identify as heterosexual and/or cisgender.

- Cisgender refers to a person who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth.

- Transgender refers to a person who identifies with a gender different than the one assigned at birth.