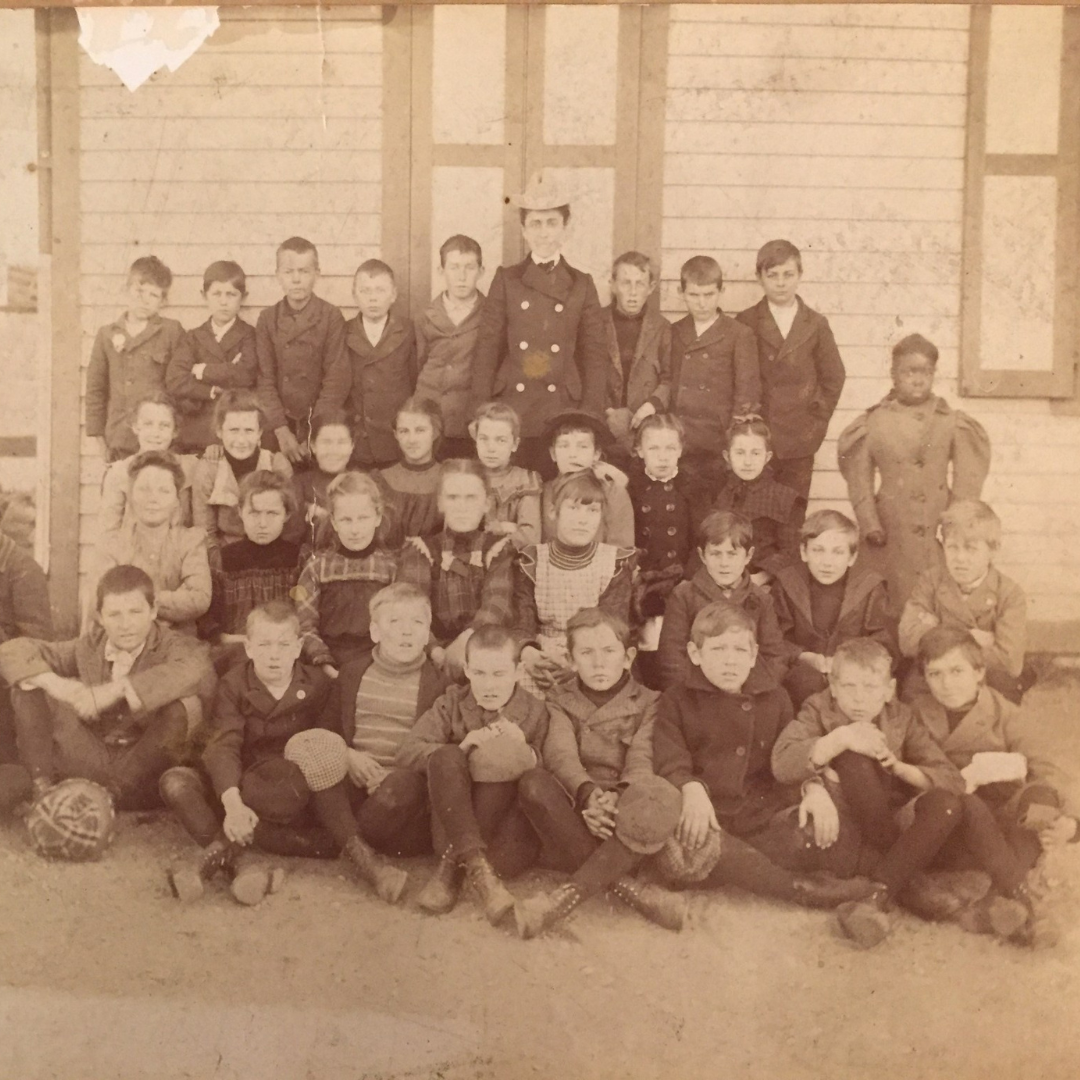

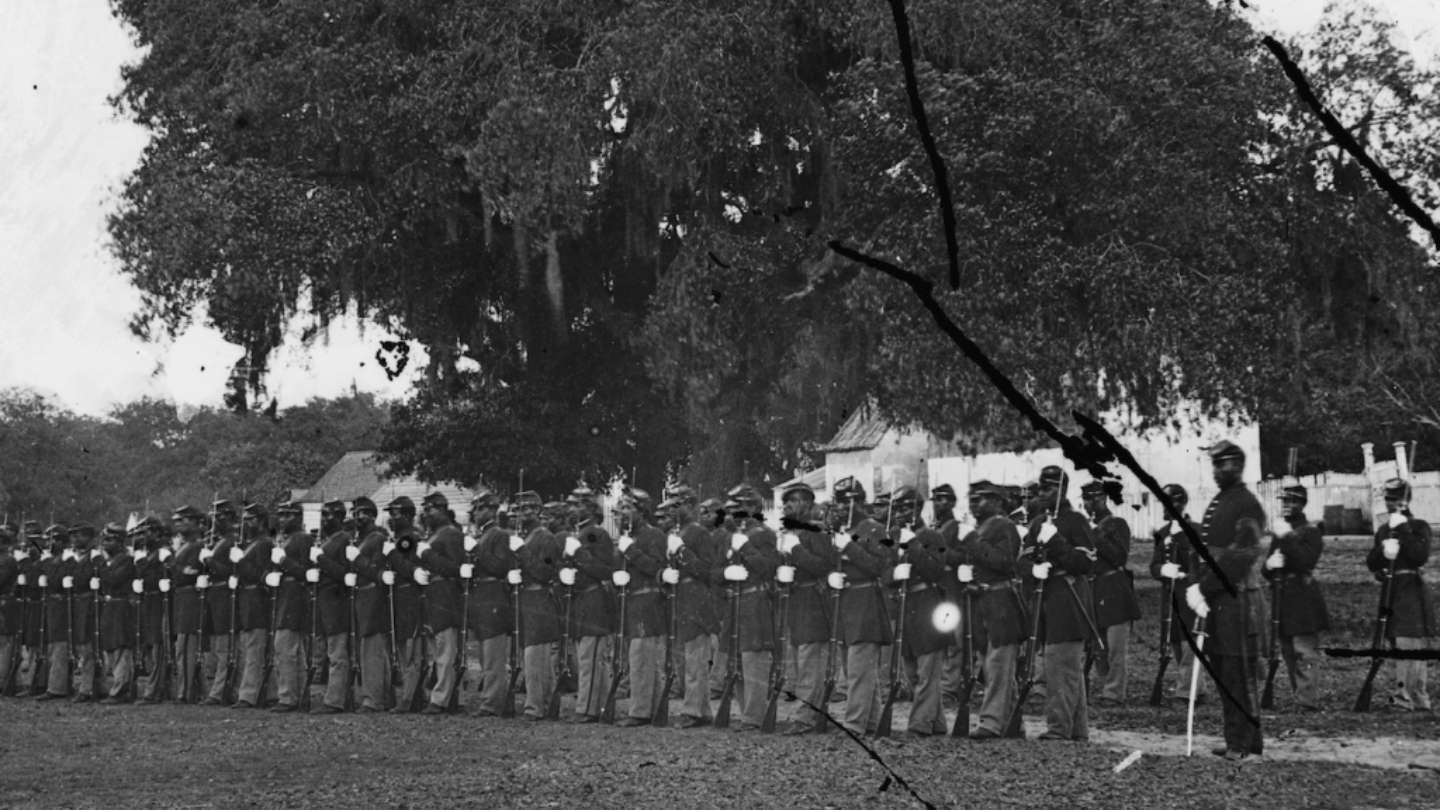

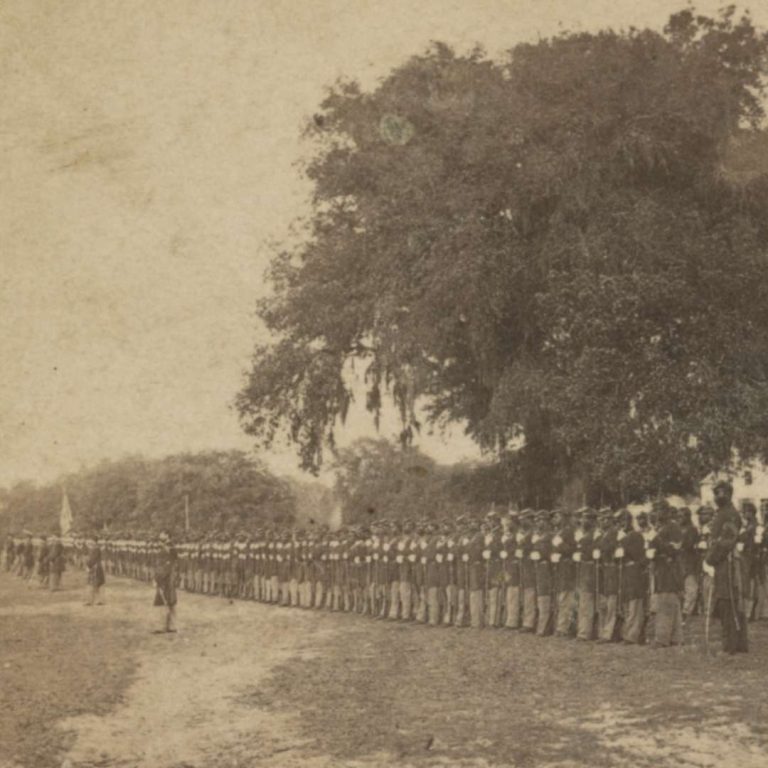

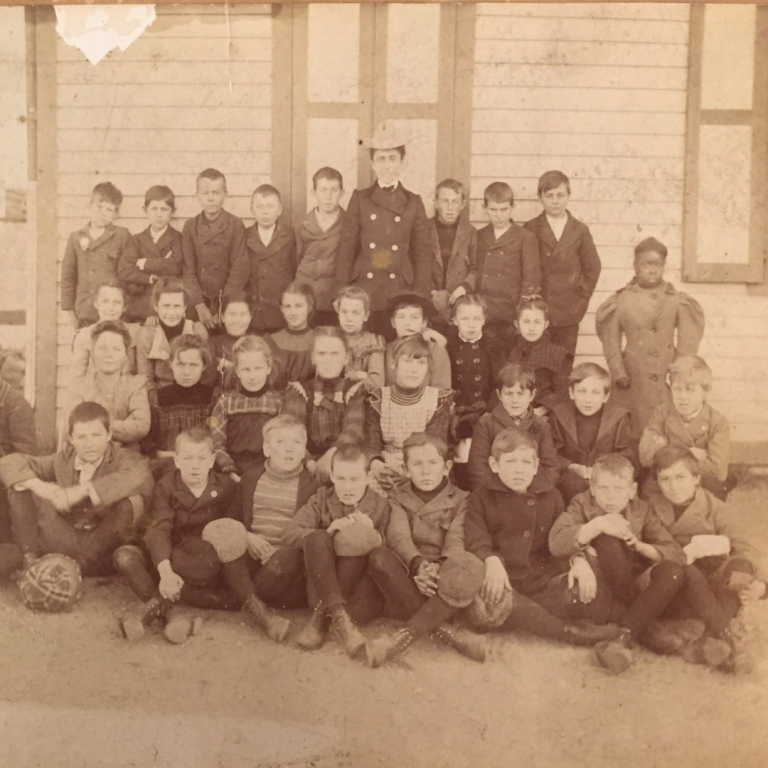

The fight for equality of education—and for respect in the classroom for children and teachers of color—in Connecticut towns can be traced back nearly two hundred years. Entrenched social biases had long created de-facto segregation within the state’s education system. In 1831, the citizens of New Haven successfully fought the opening a mechanical college for Black men and in 1833 Prudence Crandall, a Quaker teacher was arrested in Canterbury, Connecticut for opening a school for young Black Girls. In 1868, in response to a state Educational Law requiring open enrollment in public schools despite students’ race or color, the Hartford School system voted for “separate but equal” schools for non-White children.

By the twentieth century, negative attitudes toward Black students in largely White public schools—particularly in affluent neighborhoods—remained entrenched. While the active years of the Civil Rights Movement brought the legal fight against school segregation to the South, Northern communities were often overlooked for their de facto segregation of children of color from public schools.

Project Concern

In July of 1970 a group called “Westporters for Equality in Schooling” sent a letter to Joan Schine, Westport Board of Education chair. The group asked for Project Concern, a national school integration plan which brought elementary age children of color from under-resourced areas of Bridgeport into Westport schools, to be placed on the board’s agenda. A bitter fight ensued.

The program was overseen by Cliff Barton, a ground-breaking Black educator who was a former teacher and administrator with passion for looking after students with special needs—including those disenfranchised by racial inequality. Barton had joined the town school system in 1958—the same year former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt made public remarks about the need for human rights and human dignity to begin in “small spaces” including schools. ”Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination,” she wrote.

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination.

Eleanor Roosevelt, American political leader and activist

By December, the discussion to participate in Project Concern had moved to a vote. On the 7th the Board of Education passed the resolution to bus 25 African American students from grades 1 through 3 to Westport, with the final vote to pass being cast by chair Joan Schine herself.

The vote created community upheaval, and many protested the move, sparking the creation of the “Recall Committee”: a parent group formed to remove Mrs. Schine. On New Year’s Eve an article in the Bridgeport Post reported a petition with nearly 4,000 signatures was delivered to Town hall to request such a recall after Schine refused to hold a referendum. Local attitudes toward Project Concern can be viewed in the documentary film below.

The City of Hartford had already opted into the program in 1966, with its own share of push back and criticism. Opponents of the vote feared that the program would lead to a “dangerous opening wedge in an undeclared campaign to bring more and more ghetto children into Westport with consequent dilution of the quality of education.”

Today in Westport, we are engaged in a situation in which the forces and agents with the most power reign temporarily in an eternal “king of the hill” struggle.

Joan Schine, Westport Board of Education Chair, 1971

Subsequently, the Westport Board of Selectman called for a special election to remove Ms. Schine. The case went to the Connecticut Superior Court and resulted in the dismissal of the proposed recall vote entirely. Schine continued in her role as Chair and remained active in the town government. In June of 1971 Joan was quoted saying, “Today in Westport, we are engaged in a situation in which the forces and agents with the most power reign temporarily in an eternal “king of the hill” struggle.”

Where Are We Today?

Project Concern continued and expanded, evolving into Project Choice, and paved the way for programs like Open Choice and A Better Chance which continue today. Despite hard-won gains, the fight for true equity in schools continued leading one scholar to note in his article “Nineteenth Century De Jure School Segregation in Connecticut”:

“It becomes increasingly evident that Connecticut’s response to the problem of racial isolation in its public schools has been in the past and is now characterized by flashes of decisiveness and statesmanship, interspersed with periods of anguished vacillation.”

Today, Connecticut student body is almost equally divided between White and BIPOC students. Yet the state’s school districts remain highly segregated. White children largely attend schools with 75% other white children and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) children attend schools with 75% other BIPOC children. In 1996 the state Supreme Court ruled on Sheff Vs. O’Neill, finding that the Hartford School District was violating the state’s anti-segregation clauses. However, with little guidance or benchmarks toward achieving desegregation by 2003, little progress had been made.

To learn more about artists, activists, and educators who impacted Westport and our African American community visit our Remembered exhibition with the button below.