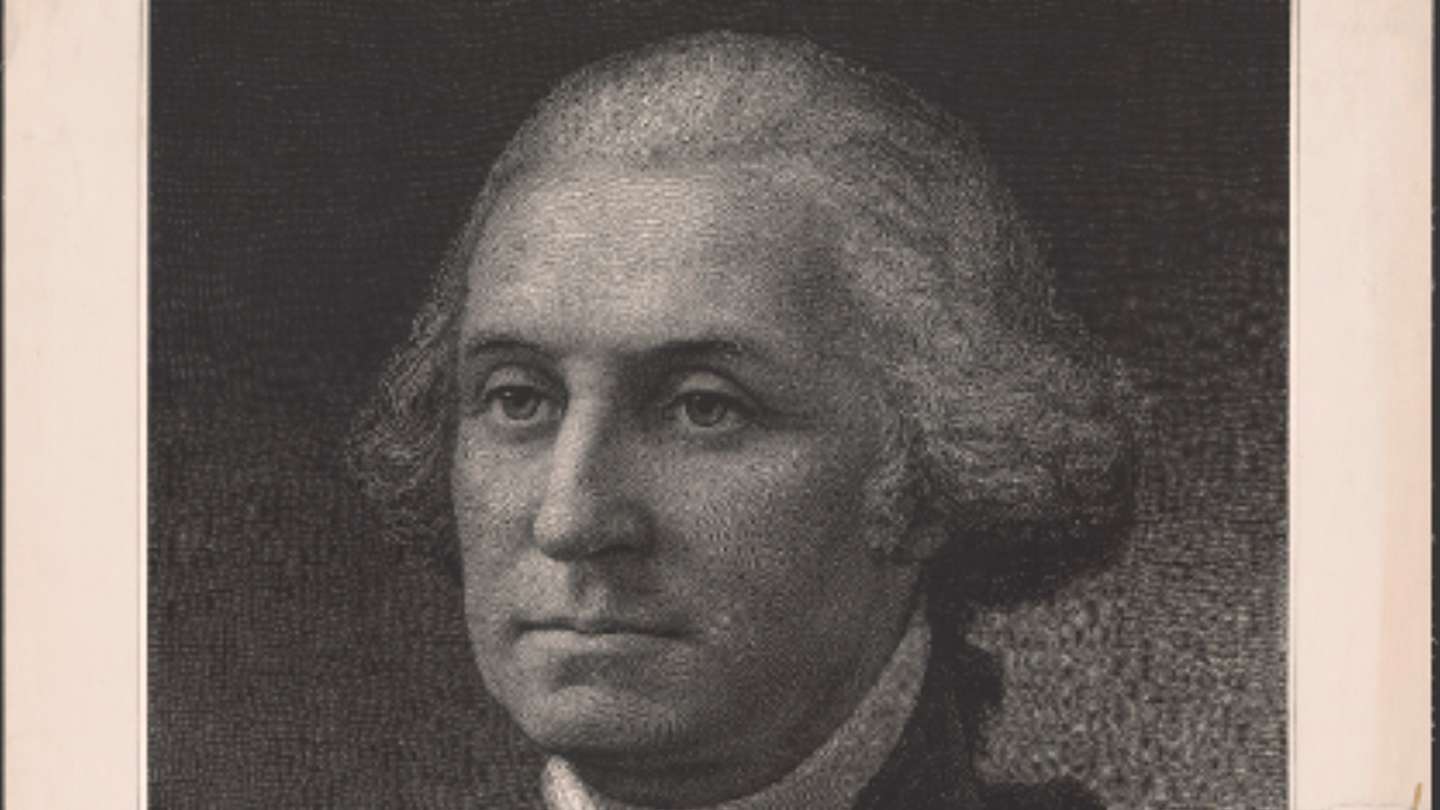

In 1992, the Museum (then Westport Historical Society) received the gift of an invitation date December 13th 1798 from President George Washington to a Mr. Sprague. Precious as it was, this gift was carefully locked away in the Museum vault and only its facsimile made public appearances.

It was, arguably, the most important holding in the Museum’s collection.

And it was also a fake.

The original intake paperwork for the gift clearly indicated that the invitation was authentic but that the signature was most likely not Washington’s. Still, lore among volunteers, staff and visitors nonetheless quickly spread that the Museum owned an authentic Washington autograph.

George Washington engraving c. 1876, Courtesy Library of Congress

The truth wasn’t discovered until almost 30 years later when a Museum staff member with an expertise in Washingtonia quickly recognized that the signature did not belong to the first president. After being taken out of its frame, the deception would prove to go even further. The signature was on the back of an invitation to a presidential dinner dated December 13th, 1798—almost two years after Washington left office.

Even though the fake was obvious, we nonetheless sent it to our colleagues at Mount Vernon for authentication. In the museum world–as in other fields such as journalism and the law–multiple sources to prove or disprove the appearance of fact are considered best practice. However, as expected, Mount Vernon quickly confirmed what we already knew (that the signature was a fraud) and what we suspected (that the invite itself wasn’t even real.)

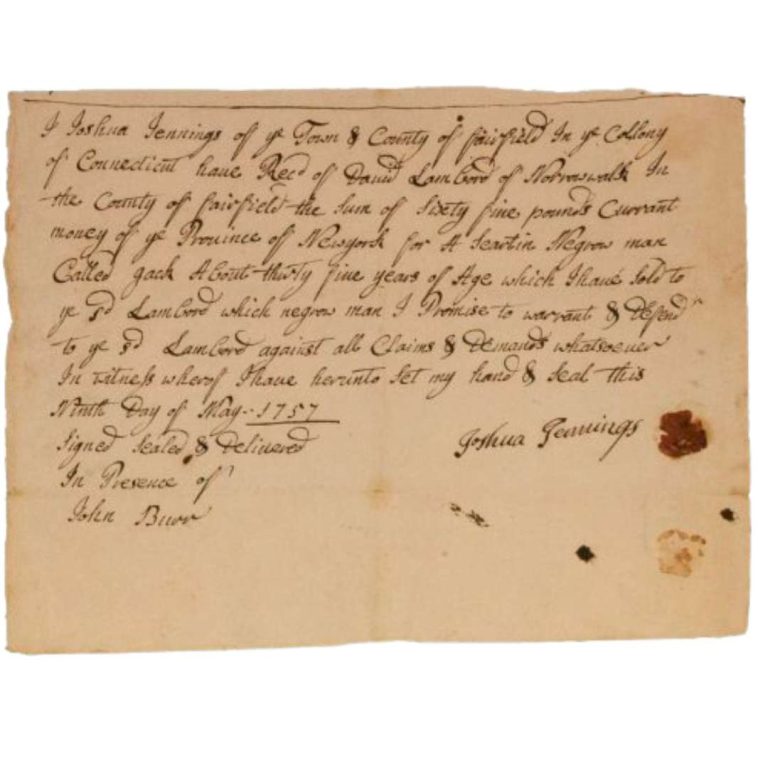

Portrait of John Adams, Courtesy of Library of Congress

Ultimately, it turned out that the printed invitation was one often used by the Adams administration—as confirmed by the John Adams Papers Project experts at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

So, who was the invited guest—this Mr. Sprague? There was a Representative called Peleg Sprague serving his last year in Congress at the time of this invite. The dinner in question was held on a Thursday—which was in fact the customary day of the week for official Congress dinners first held by Washington and later, Adams.

More intriguing, Washington was in Philadelphia (then the nation’s capital) as was President John Adams December 13th 1798. Washington was there to raise an army for what the government believed might be an impending invasion by France. Washington’s diaries indicate, however, that he dined alone in his rooms on the day in question.

Presidential dining as depicted in the A. Alfred Taubman Gallery of the Donald W. Reynolds Museum, Courtesy mountvernon.org

Grains of truth (the date; that it was a real invite of the Adams era; the presence of all parties in the capital city on that date) lent veracity to what was, essentially, a false representation of facts. No doubt Peleg Sprague was invited to official dinners on Thursdays by President Adams but he certainly wasn’t invited to one on this day by George Washington.

Coincidentally, another Sprague– William B.– was a known autograph collector and the first person to gather the signatures of all the signers of the Declaration Of Independence. At the time of his death, he had amassed over 10,000 signatures including those written upon an impressive array of presidential pamphlets, papers and invitations.

But in 1798, the date of our invitation, William B. Sprague was only 3 years old.

Is it possible that our document was a humorous conceit on the part of the later autograph aficionado Sprague? Or was it something more nefarious—someone’s carefully, curated document presenting a limited perspective because there was little fear that it would be picked apart and the fraud discovered?

Indeed, the trickery might not ever have been made plain had someone not come along to question what was presented and taken for fact.

Now, the value of our “Washington signature” centers not on its veracity but in the success of its deception. It is proof of how a lie, well told, can become the truth—at least in the minds (and sadly pocketbooks) of some.

Despite the corroboration of experts, there are still those who hold dearly to the idea that the signature we own is an authentic Washington. We can understand why—it’s hard to relinquish carefully held ideas built around our own fervent beliefs but, in the end, facts will out.

In honor of President’s Day visitors can see for themselves this and other scams at our next Tuesday Treasures—Counterfeit History: Fun With Fakes & Phonies, Tuesday, February 4th at 6:30pm.