As rice showers down, the happy couple runs to a car donning cans and ribbons along with the words “Just Married” sprawled across the back window. Smiling ear to ear, the groom disappears into the cab followed closely by the bride pulling her long white skirts around her.

This classic scene is what many of us picture when we think of a wedding. The white wedding dress is probably the most significant part of the scene but has this always been the case? White wedding gowns in a variety of materials and styles are held in countless museum collections across the globe including Westport Museum. But these ideals of bridal wear, along with the social definition of marriage, have been constantly changing throughout time.

The Iconic White Gown

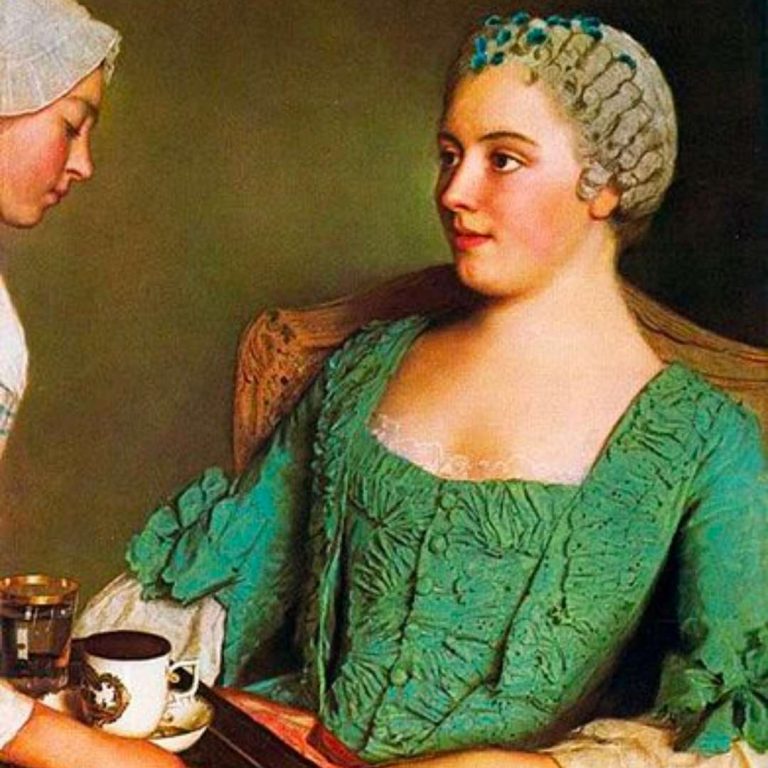

White can symbolize virtue, purity and innocence in Western countries such as the United States in the 21st century, but in the past the color white specifically symbolized one thing: wealth.

Until synthetic dyes and electric washing machines became widely available in the 20th century, keeping clothing clean was a laborious task. Fine white textiles, especially with fragile lace, silk, and satin used only for one occasion would have been unfeasible for most. To marry, women of middle and lower classes would wear their “best dress,” usually in a shade of brown. Colors such as grey or light purple could be multifunctional as both wedding and funeral gowns.

White as the ideal wedding gown color spread in the 1840s with the publication of Godey’s Ladies Book. Although white was a wedding dress color among royals and the wealthy prior, Queen Victoria’s white wedding gown worn in 1840, became the ideal because of widely distributed media coverage of the nuptials of the young British Queen. Today Victoria is still credited with the “creation” of the white wedding dress.

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom wed Price Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on February 10th of 1840. Her white gown was made with materials manufactured in Britain to bolster the country’s silk and lace trades. (The Royal Collection Trust)

Changing Definitions

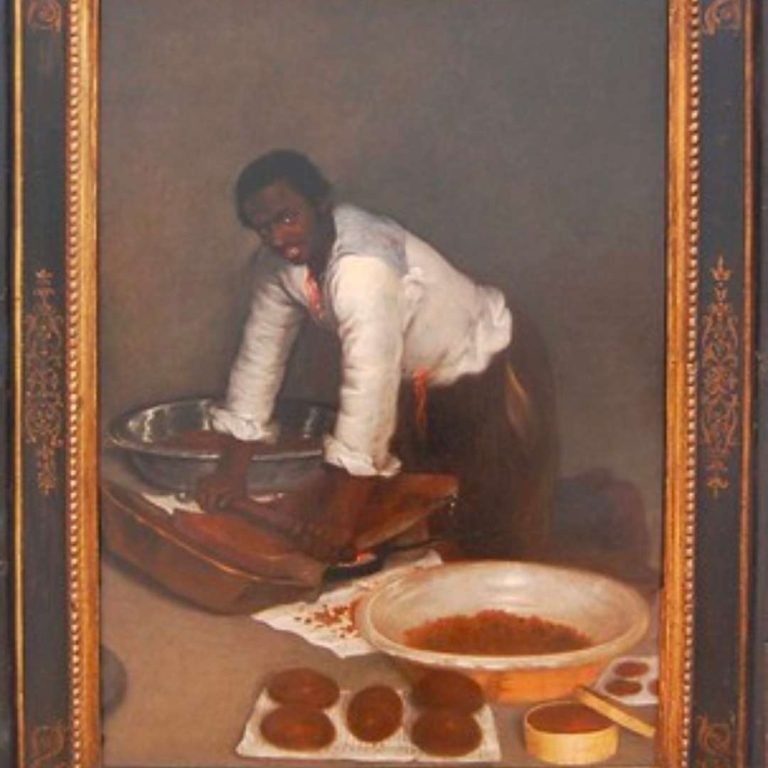

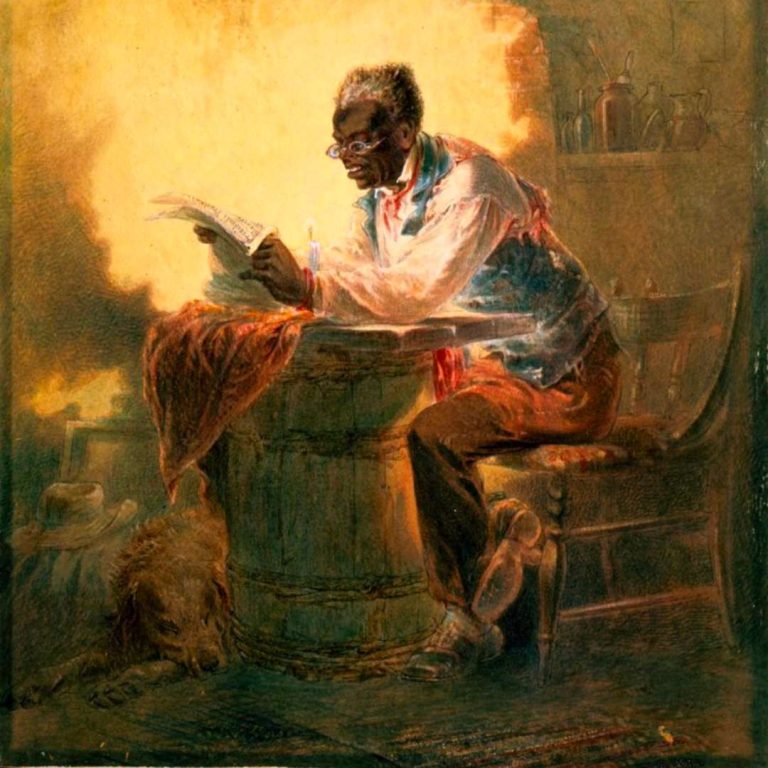

Just as the use and symbolism of white in weddings has evolved so has the social understanding of a marriage contract. Marriage as a legal agreement has existed for millennia, usually as an agreement between the father of the bride and the groom—with the father literally handing off his daughter to her husband. These marriage contracts, and their subsequent wedding ceremonies, were legally a transfer of assets—the woman—from one man to another.

In Westport in the 18th century a White woman could not own property, make contracts, or vote—women of color and immigrant women held even fewer legal protections. Legal contracts such as marriage did little to safeguard women through the 19th and 20th centuries; Women entering a marriage contract were free to do so under their own legal power in the mid-20th century. Throughout history “concubine marriage” allowed couples to engage in intimate relations and co-habitation when differences of religion or race did not allow for legal matrimony. Concubine marriages were formed by contract, meant to financially protect women, and sometimes her children, in the event of separation.

Opening Reception

Visitors explored several examples of wedding gowns—both white and the less traditional—in the Museum’s exhibition opening on March 10, 2023. Not only did our community get to admire these gowns in detail but also discovered how these iconic dresses relate to wealth, class, gender, and women’s rights.

Visitors enjoy the interactivity of the exhibit as well as the gowns themselves.

Our textile collection contains over 1200 individual pieces; these gowns are fine examples but represent such a small part of our holdings. These gowns not only exemplify the changing silhouettes of bridal fashion but also the changing nature of women, and those presenting as female, in our society.”

– Nicole Carpenter, Programs and Collections Director

Many enjoyed creating their own wedding dress through the exhibit’s interactive magnet wall, highlighting wedding fashions from around the globe and how individualism is encouraged in multicultural ceremonies today. Explore our exhibit yourself through November 11, 2023.