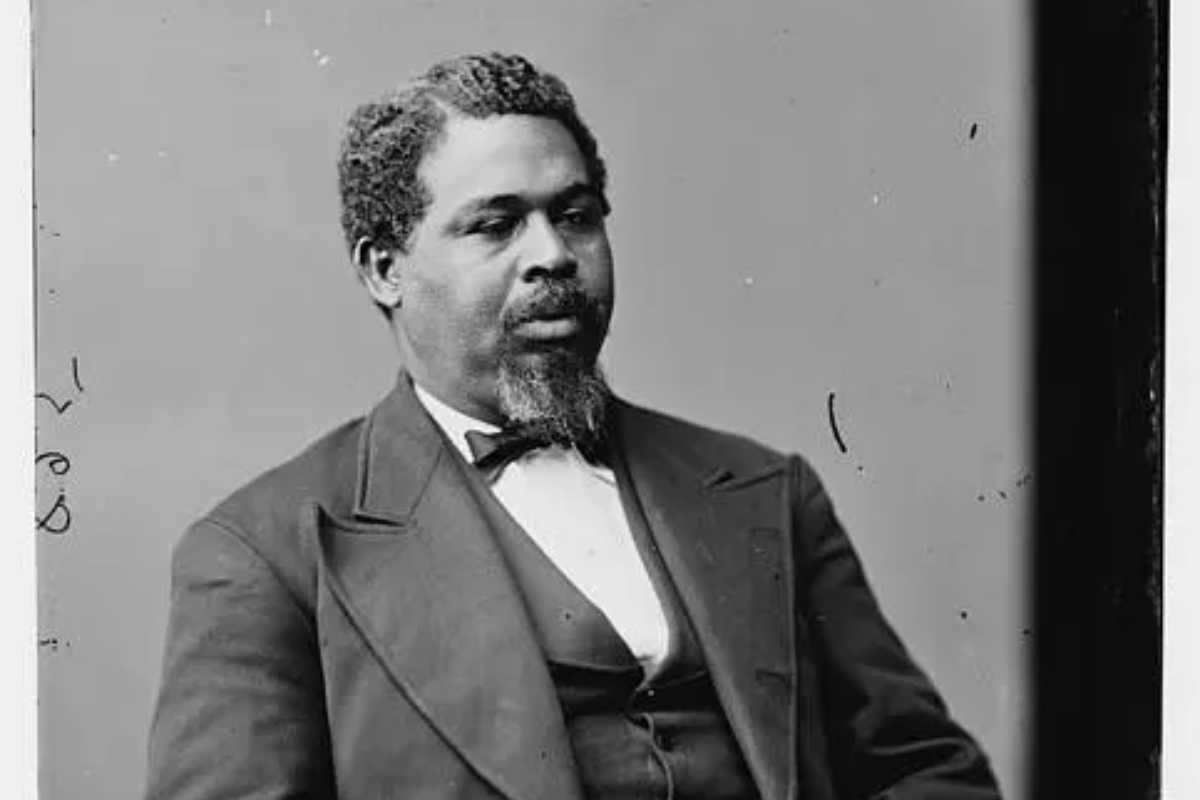

African American life in Westport—and neighboring towns—represented a wide diversity of experience. We can piece together details of their daily existence through the records of local churches and the account ledgers of local stores such as Judson’s which stood somewhere on Beachside Avenue Westport and Southport. The earliest free people—and enslaved people as well—were given purchasing credit for goods paid for by cash, barter, or labor. In some cases, the labor of enslaved people was used to pay the accounts of their owners.

From landholders like Henry Monroe to Mary and Eliza Freeman, who were born and raised in Derby built homes in the prosperous free black community in Bridgeport called Little Liberia, 19th- century African American families spanned the social spectrum.

Others came to towns like Westport from the South during the Great Migration of the 1930s to find work in the local farms, and as domestic servants in lavish estates like Hockanum and the Laurence Estate (Longshore). Many people lived in the downtown area on Bay Street, Wright Street, State Street (the Post Road), and East Main Street. Most of the residents there are listed on the 1940 census as working in service professions.

In 1950, a suspicious fire razed 22 1/2 Main Street, a boarding house exclusively catering to African American Westporters. Townspeople speculated that the fire was caused by a firebombing specifically designed to drive black residents away. Just a few months earlier in December of 1949, an RTM hearing about low-cost housing in Hales Court drew interest because of the attendance of “a delegation of Negro residents.” The front-page photo in The Westport Town Crier ran with the spurious caption “For the first time in Westport history, a Negro attended one of this community’s town meetings.” African American Westporters had come to the meeting to ask if they were eligible for town housing, describing their home at 22 1/2 Main Street as “slum quarters”. The Westport Housing Authority Chairman said they were eligible “after veterans with proven needs and any others whose needs proved more pressing than theirs.”

The fire at 22 1/2 Main Street coupled with discriminatory real estate practices effectively heralded the end of an established African American community in Westport.

Dr. Judith Hamer, who moved to Westport in 1971 with her husband and daughters, specifically recalls only being shown homes listed with realtors who were willing to work with African Americans. In the 1980s, her husband Martin Hamer, a writer for IBM, wrote a column entitled “Trying to Love America” for the Westport News, and often explored issues of race relations and life as a black man in suburban Connecticut.

Like the Hamers, other African American Westporters, such as doctors Albert and Jean Beasley, beloved pediatricians who worked for many years at Willows Pediatric, and local business owners, Venora and Leroy Ellis, were successful and prominent. Mrs. Ellis was a dressmaker and house couturier while Mr. Ellis was a successful performer who served in World War II in the USO in the South Pacific, performing as a singer with the DePaur Infantry Chorus.

The Ellises remained in Westport for more than sixty years overcoming racial prejudice in a community that had come to forget the role of the black community in the very founding of the town. Venora Ellis and Dr. Albert Beasley were recipients of Trailblazer Awards in 2009 and 2010 respectively given by TEAM Westport, the Town of Westport’s diversity action committee.