Giving space and thanks for the cultural gift of our Native communities.

By Ramin Ganeshram

From the window of my office at the Museum, I can see the tops of the trees near the Saugatuck River a little over a block away. When the Bradley-Wheeler House was built, over two-hundred years ago, the riverbank was closer, curving in toward Main Street where Parker-Harding plaza now stands. Gazing from this vantage, you would have seen small shops with docks jutting out behind them into the water.

Cast your mind back further another two centuries and you’d see old growth forests crowding the river front, featuring trees and other fauna long ago extinct. Up and down the embankment, all the way to the mouth of the Long Island Sound, the native Paugussett Nation camped in small clearings during the warm weather, taking advantage of the rich oyster, clam and fishing grounds. Later, when the autumn chill set in they would return inland to protected valleys and forests to settle in for the winter.

Their unceded lands, never legally given away, were centered in what is today Orange/Milford and extended south to what is, today, Greenwich and north through Eastern Litchfield to the Massachusetts border. The Paugussett people—and forty million other indigenous people who called North America home before European contact—are much on my mind this Indigenous History month. I find myself mulling the story of the First Thanksgiving, its mythology and its less-pretty truths which we explored in the first episode of our podcast Buried In Our Past.

The story we hear about that first harvest celebration is a Eurocentric one. Period accounts of tribal people adhere to a European world view. In a letter describing the first Thanksgiving in Plimoth in 1621, Edward Winslow wrote:

…it hath pleased God so to possess the Indians with a fear of us, and love unto us, that not only the greatest king amongst them called Massasoit, but also all the princes and peoples round about us, have either made suit unto us, or been glad of any occasion to make peace with us

Winslow goes on to say that the presence of the English also influenced native people to put aside tribal conflict in favor of uniting under the English king. His inaccurate missive was not so different from Columbus’ 130 years before who wrote that the “timid” “guileless” and “fearful” nature of the native people he encountered in the Caribbean would make them easy to conquer.

If we are to take the word of European “settlers”, the indigenous people of New England and elsewhere were largely in awe of them—their clothing, their tools, their boats, their appearance. Allegedly eager to please, native people were quick to engage Europeans and learn their “superior” ways. In this version of the story, those from the Old World were bringing their advanced culture to the “new” one.

But what if the colonists world view is actually the simplistic one? The one that is “timid” and as Columbus first wrote “full of terror” about perceiving and accepting new things? What if we look at the whole exchange from a different angle?

What if we started from the premise that the international sophisticates in this scenario were the native people whose worldliness and tolerance allowed the myopic settlers to make their dream of a new England become a reality?

To do this we have to understand that Indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere—in what is now North, Central and South America—are not a monolith. Theirs are unique cultures thousands of years old. Each of these cultures embraced a cosmology that was expansive and, in various degrees, understood a world of possibility fashioned by a Creator.

This meant that the concept of other human beings, living other types of lives, would not have been surprising to them. They saw this among their respective nations—different clothing, different ways of eating, different languages, different family systems, and different ways of farming, hunting, gathering, eating and drinking. What Europeans perceived as fear, or awe, was more likely often the circumspect observation of something unknown and prudent caution.

Land usage for these communities was based upon accepted cultural norms—and these, too, differed by tribe or nation. While the sense that no human being owned the land was fairly universal, rules outlining the rights to use the land certainly existed.

Accounts by Columbus and others tell us that when those first Europeans arrived in their massive ships, indigenous people often rowed out in canoes to meet them. Was this “guilelessness” or was it the natural curiosity of culturally advanced people who understood there was more to the universe than their realm? Native Caribbeans had mastered sea travel in their own small canoes (in fact the word “canoe” is Kalinago/Carib). No doubt they would have recognized a ship as a much larger version of a watercraft.

And their well-documented willingness to share food and goods with colonizers—was this a desire to please or, as it was in their own communities, an overture of understanding—the opening salvo to diplomatic engagement that was mis-read by Europeans who had come from a proscribed world view?

Within and among tribes, negotiation and diplomacy were well established tenets—hence the restraint of many First Peoples when encountering Europeans, choosing not to use force but to approach with an open mind. This world view enabled native people to quickly adapt to their new forced reality with Europeans, not just through trade but self-defense when required or by colonizer’s rules.

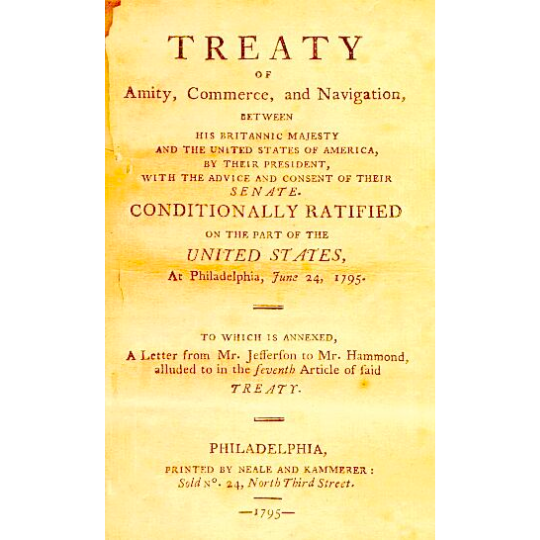

Here in Connecticut, tribal people attempted to use English law to secure their homelands. In a savvy appeal to the self-stated European world order, native leaders petitioned the colony’s general court in 1659 in what would be the first of such attempts to litigate alleged land sales and protect native usage rights.

In what is now a well-documented story of hypocrisy, that first suit was denied, instead granting the Paugussett’s an 80-acre tract that eventually dwindled down to a mere quarter acre over time. Similar proceedings throughout colonial America would end much the same way. You can read about the Mohegans 1789 petition to the Connecticut General Assembly in Connecticut Explored. And, check out the Worlds Turned Upside Down podcast from our colleagues at George Mason University, for an excellent deep-dive into the complexity of tribal alliances, legal proceedings and rules of engagement—especially how they influenced commanders and politicians during both the French & Indian and Revolutionary Wars.

What followed Columbus, the Pilgrims and others misguided sense of superiority is undisputed: Decimation of the tribes through European colonization through war and disease. Those who accept historical fact also accept that the First People of the Americas were the ultimate victims to European greed, followed closely by Africans enslaved to develop their stolen resources.

But, what is less known to many here in Westport—and hundreds of other small New England towns—is that they are still here, limited in number but holding on to their culture, their language, and maintaining connections to their tribal homelands. At the Museum, we give space to this cultural continuance. It is one of the many reasons we begin our programs with a land acknowledgment—out of respect for those who are still here. And in thanks for the sustaining gift of their presence against all odds. You can learn more about the tribe in Charles Brilvitch’s History of Connecticut’s Golden Hill Paugusset Tribe available in the Museum’s gift shop.

Join us this November and throughout the year as we continue to explore the original traditions of this land. On Tuesday, November 5th we’ll be hosting Golden Hill Paugussett Clan Mother Shoran Waupatukuay Piper for a Native Healing Workshop where you will learn how to create a soothing salve ointment through this rare hands-on experience. On November 23rd, join us for a program to dedicate outdoor interpretive signage sharing a larger history of the tribe. Learn about Native winter observations at our 2nd Annual Cultural Fellowship Night on December 12th.