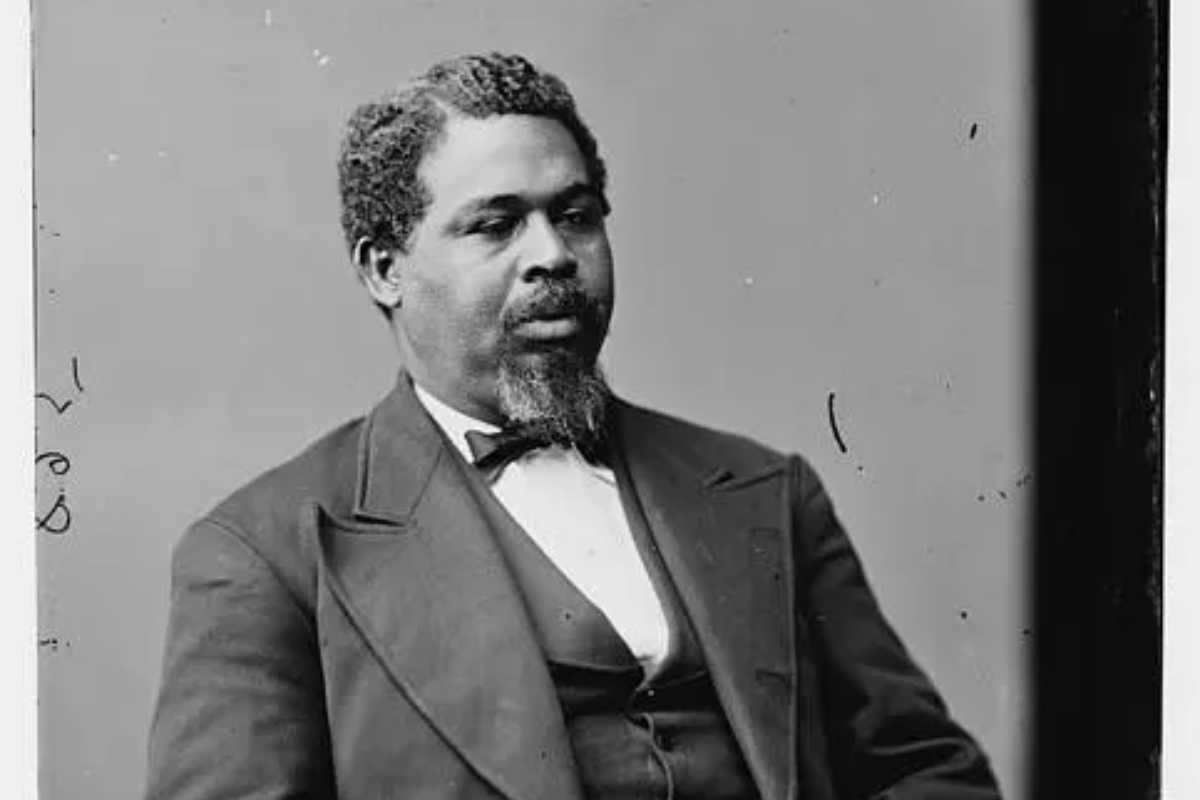

Originally hailing from Charleston, South Carolina, where he may have been an enslaved person, Benjamin Adair was one of just a few prominent Black landowners in Westport during the 19th century. While the exact circumstances of Adair’s previous life are unknown, the Freedman’s Bank Records in New York note that he was the son of Robert and Sarah, who were listed without surnames.

By 1850 Benjamin Adair was working as a waiter in the New York City home of prominent banker Morris Ketchum who would later help finance the Union Army in the Civil War. Ketchum would eventually go on to own an 18th century Westport Estate called Hockanum, where Adair was listed as a coachman in 1860. Adair’s wife, Ursula Mingo, was African and Native descent with family ties to the Shinnecock Reservation near Southampton, Long Island.

Ursula and Benjamin met in New York and married prior to coming to Connecticut. Ursula seems to have grown up on or near the Shinnecock Reservation. She was one of five children born to Horace Mingo and Eliza Cuff. Ursula and Benjamin would themselves have six children. They were Laura Pheobe, Ursula, Emily, twins Benjamin Robert and Eliza, and Samuel. The twins died young with Benjamin being just under one year old when he passed away and Eliza was about seven and a half. They would also lose their son Samuel at the age of twenty-five.

Once the Adairs’ reached Westport their fortunes would dramatically change. Mr. Adair purchased his first property on Franklin Avenue in the Saugatuck area of the town in 1852 from Sydney Miller. The property was adjacent to a parcel owned by his boss, Morris Ketchum. A savvy businessperson, Mr. Adair later sold the property to the New York and New Haven Railroad, which was then expanding up the Connecticut shoreline for a massive profit.

Continuing to build his wealth in real estate, Benjamin Adair then purchased about 9 acres of land from Morris Ketchum in 1877 across the road from the Hockanum property at what is today known as “Glynn’s Corner”–the intersection of Main Street, Route 136 and Route 57 (Weston Road).

For the next 70 years, the Adair family made their homestead a working farm while patriarch Benjamin continued to work for Ketchum. The 1880 Agricultural census shows that their small farm produced 5 tons of Hay, 40 bushels of Indian corn, and 30 bushels of potatoes. They also had cows and used them to produce 300 pounds of butter and their chickens produced 50 dozen eggs. Benjamin’s son Samuel ran the family farm.

A prosperous man during his lifetime, Benjamin Adair was able to leave a sizable estate to his wife and daughters, when he died in 1891, aged 65, due to “Intestinal Tuberculosis (contributing: Dropsey)” his son Samuel having tragically died of Tuberculosis just a few years before his father leaving a widow, Hester who was also his first cousin as well as their young daughter, Emily.

For a while, the family of women continued to live at the homestead until, in the 1920s problems began to arise. The daughters and granddaughters of Benjamin and Ursula were struggling to pay the taxes on time. The elder daughter, Laura, responsible for making the payments no longer lived in Westport, she had moved to a home in Brooklyn, NY and continued her school teaching career. Tax liens were placed on the property but then were paid within a few months.

That changed in 1937 when the land value of the estate inexplicably jumped from $4,644 in 1936 to $7,740 in 1937 while none of the Adairs’ neighbors saw this increase in land value or tax assessments. At the same time, the Merritt Parkway was nearing completion practically in the Adairs’ front yard—a circumstance which should have dropped their property values instead of increasing it.

From that point forward, the heirs of Benjamin Adair would struggle mightily to pay the taxes. In 1946, with five years of back taxes owed (a total of $828.60), the Town of Westport seized the property and auctioned it off to the highest bidder.

Benjamin and Ursula’s daughters still went on to have interesting and successful lives, but as black women in the early 20th century they faced obstacles to their success. The eldest Adair daughter, Laura, became a schoolteacher at public schools in Connecticut as well as in Brooklyn, New York. She never married, and when she passed away in 1933, she bequeathed a home in Fairfield to her youngest sister, her share of the family homestead to two of her nieces, and land on the Shinnecock Reservation to her niece Alice Burbridge.

The second daughter of Benjamin and Ursula, also named Ursula, married William Dorsey and they built a home in Saugatuck on Davenport Avenue. They had two daughters, Cynthia (a schoolteacher) and Edith (an interior designer). Edith also had two daughters, Marian, and Cynthia.

The Adairs’ third daughter, Emily, married John Vincent and they made their home at the family farm. They had two daughters who survived to adulthood, also losing two daughters and a son in infancy. Their daughters Ruth Cordelia and Alice Viola/Violet each became teachers. Alice married Edwin Burbridge. Their only child, daughter Marguerite Doris Burbridge, would go on to become an internationally renowned dancer who went by the stage name of Mika Mingo.

While the Adair family home still stands on part of its original property it has been massively renovated and added over the years to be unrecognizable today. After the property was sold at auction, the son of the next owner subdivided and sold off all but approximately one acre of the original nine that comprised the farm. There are several housing developments on the land currently.

Today, Mika Mingo’s daughter Annette T. Thomas who is also a dancer, lives in Florida with her husband Timothy. J. Thomas. She teaches classical ballet technique as applies to figure skaters. Thomas has three children who comprise the 5th generation of the Adair Family. Thomas’ daughter Heather Thomas Flores is an anthropologist working to identify and understand the power dynamics of systemic racism. Daughter Rachel Davis (nee Thomas) is an artist and interior designer with two young children—the 6th generation of Benjamin Adair’s Family and son Brendon Thomas, lives in California where he is an executive at Paramount Pictures.