By Ramin Ganeshram, Executive Director, September 3rd, 2019

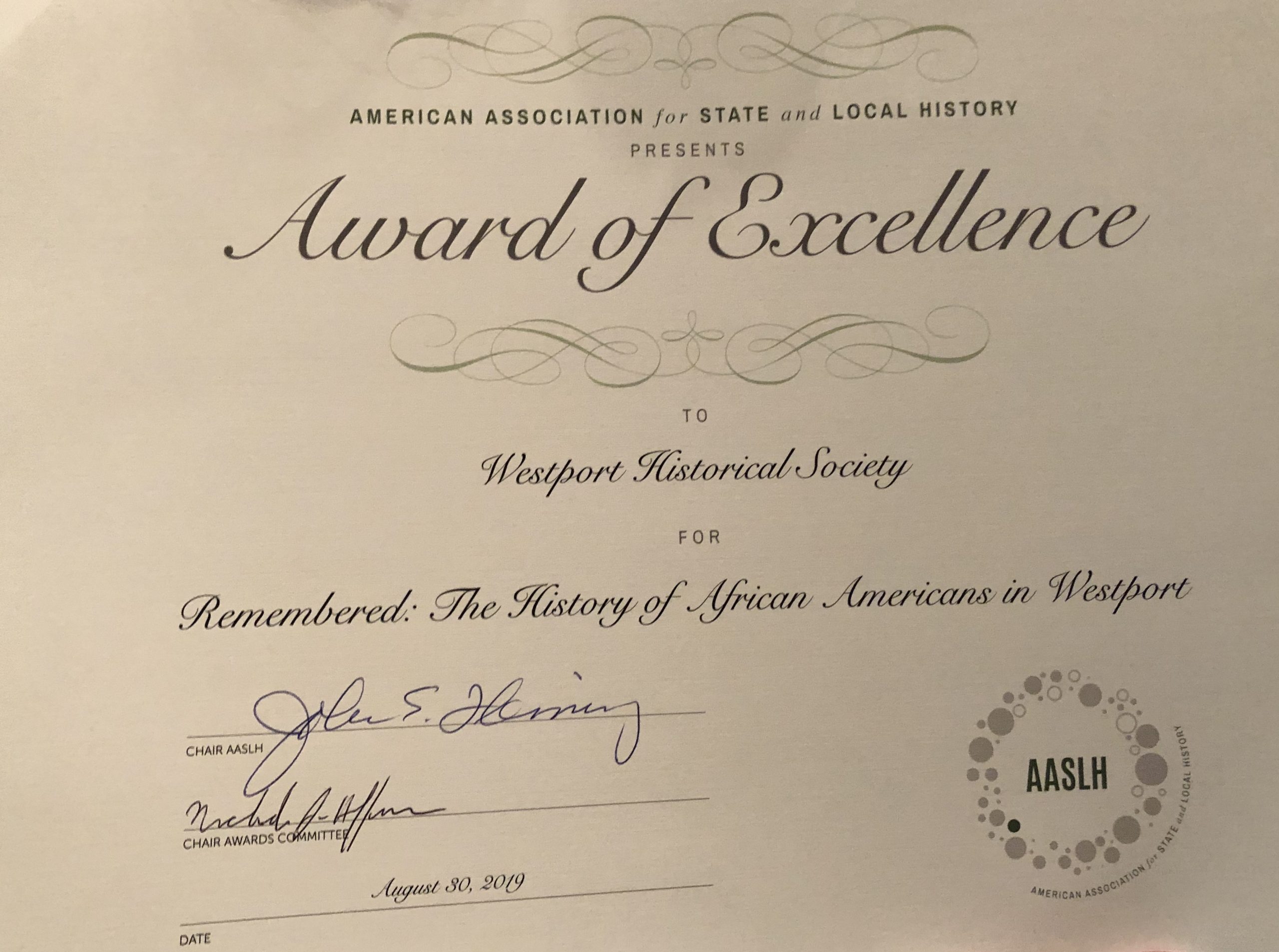

This past Labor Day weekend, while folks were rushing to and from vacation spots we at WHS were taking a trip of a different kind: Myself and board chairperson, Sara Krasne, headed to Philadelphia to receive a prestigious national award for excellence in the museum field.

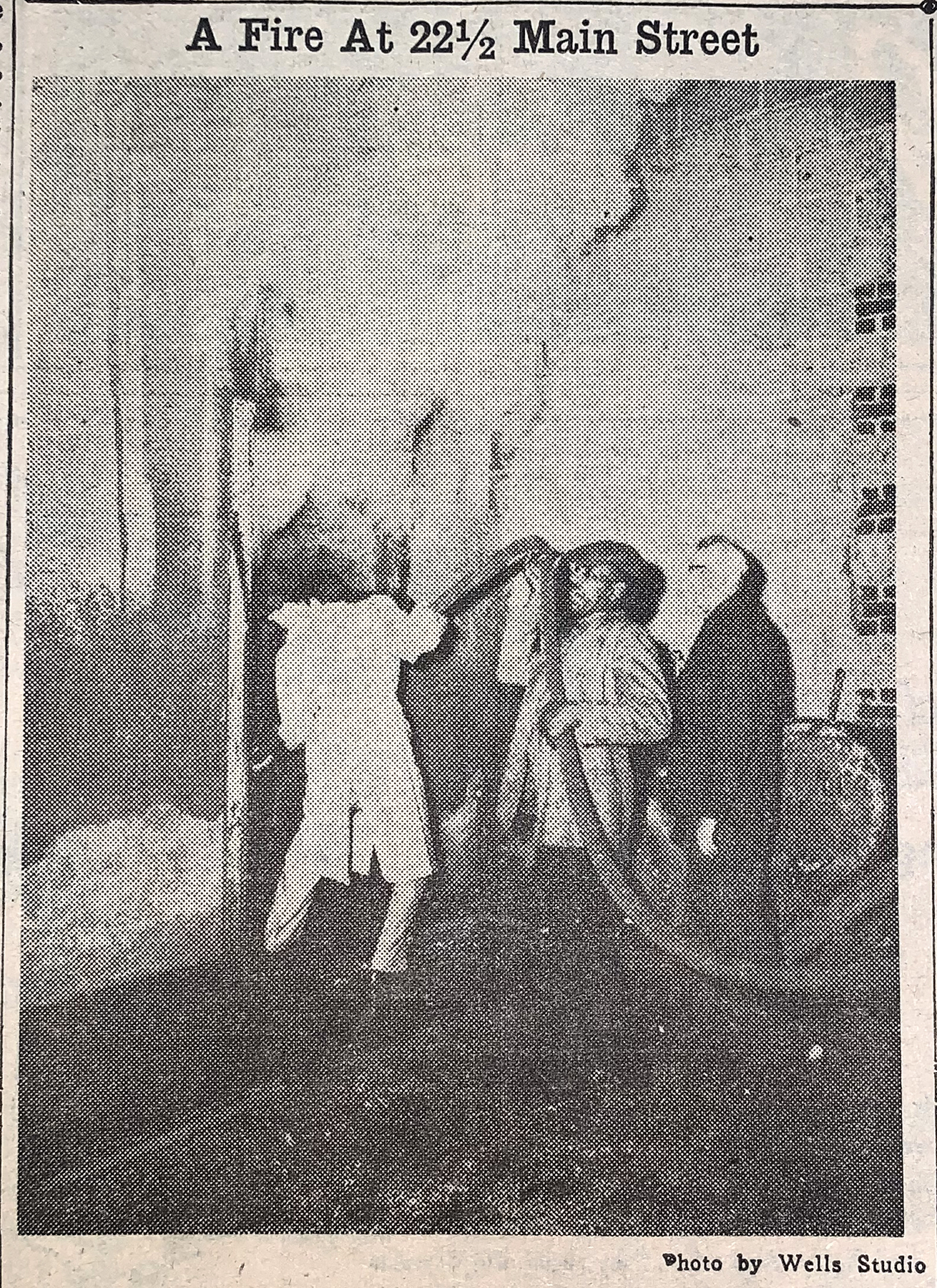

The award was for our 2018/19 exhibition Remembered: The History of African Americans in Westport which told the story of the significant contributions, achievements and struggles, of black Westporters to the town from its 17th century settlement as enslaved people through to the present time. By examining our colonial New England town, we were able to tell a story that resonates nationwide

It was particularly special to receive this award in Philadelphia—the heart of America’s movement toward Independence and its second capital city.

Perhaps what was most awe-inspiring was being in the same company as museums across the country doing excellent work unearthing the hidden histories of a wider group of Americans than ever before—women, people of color, LGBTQ Americans and differently abled individuals.

Together we are following the charge of cultural organizations—particularly history museums—nationwide to re-examine the past in a holistic way, using primary source material and rigorous research to tell those stories that have been erased.

For many this begs a bigger and quite legitimate question: Why?

Why, many have asked us, not leave well enough alone? Why re-examine a history so many have come to know and love? Why drag “skeletons” out of the closet?

At the simplest level, we are following the standards of the most respected governing institutions in our field such as the American Alliance of Museums which advocates that organizations like ours “conducting primary research do so according to scholarly standards.”

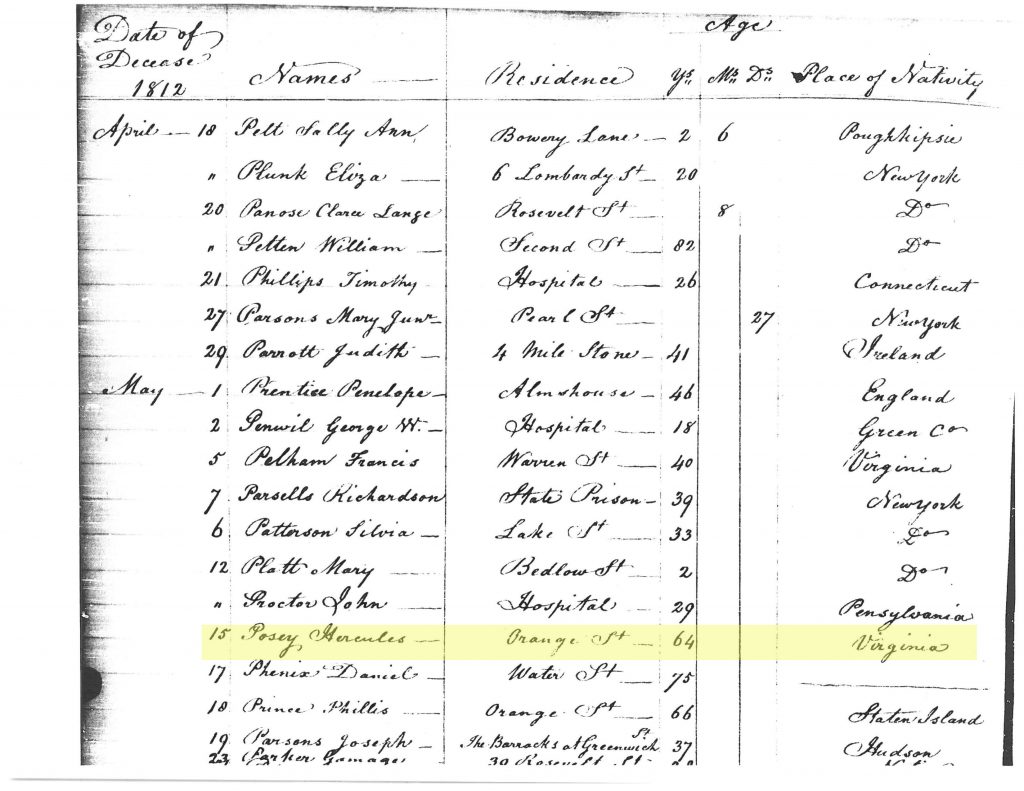

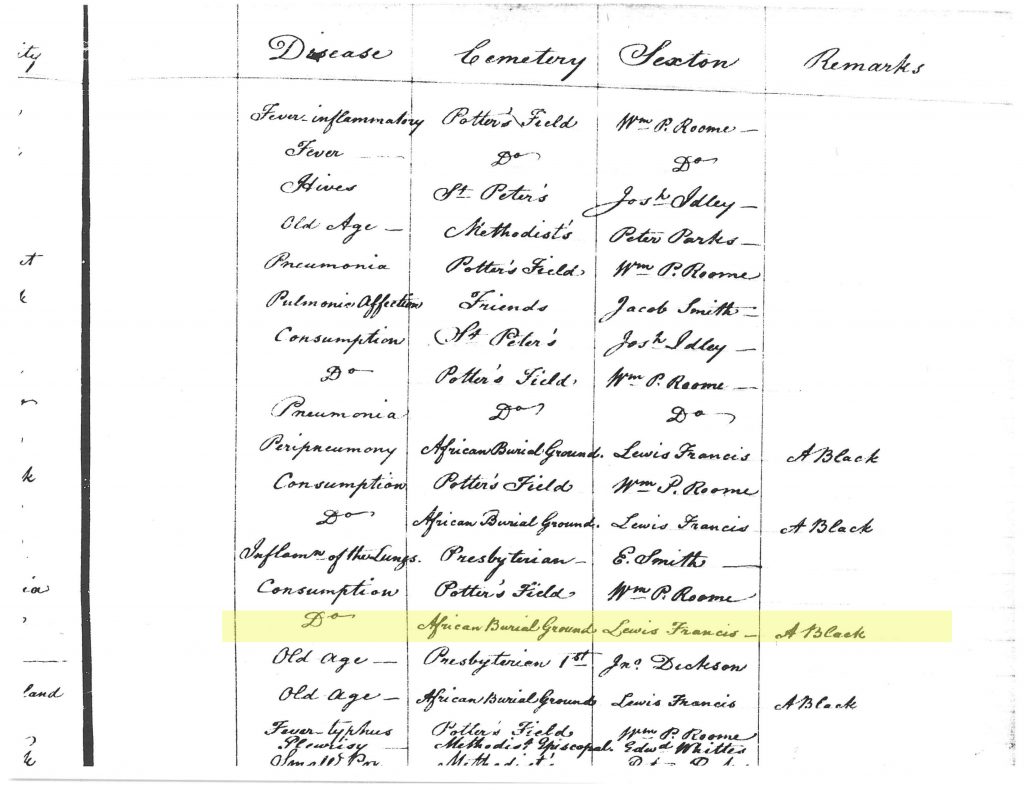

In other words, we use original documents and documentary evidence to present the facts of what happened way back when. Unfettered by a need to editorialize or cast themselves in any light other than the norms of their time, the writers and recorders of this material were, for the most part, purely honest about what happened and how they felt about it.

In pursuing these practical goals as defined by those with the best professional knowledge, we reap greater rewards. We are lucky enough to do work that creates a more inclusive community—that leaves no one out by showing that everyone’s stories matter.

That “someone” could be one of the original Bankside Farmers or a Native Pequot person driven from their land or an enslaved African American in Greens Farms or a Jewish landholder forced to flee Manhattan during the Revolutionary War because of abuse at the hands of the British. It includes artists, performers, merchants, laborers, immigrants, mothers, fathers, activists. It encompasses the most prominent Westporters as well as the most invisible ones.

Our work—and our charge as a museum—is to fill the gaps in our history with untold truths that make our community whole.

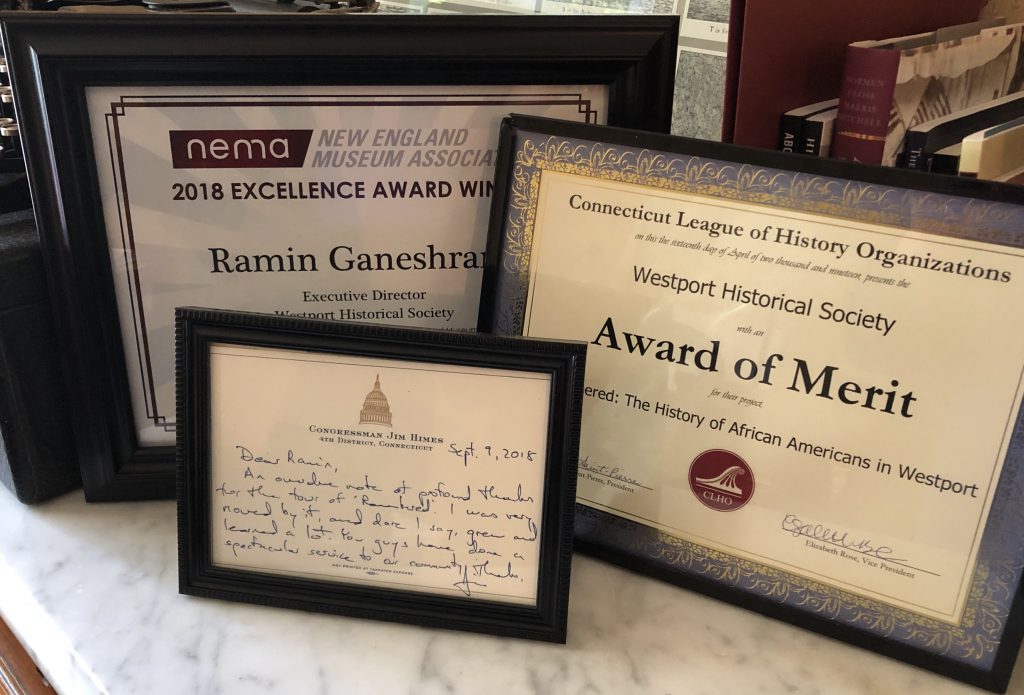

It’s work that doesn’t end and isn’t always easy but we’ve been rewarded with recognition that keeps us going. In the last year WHS has won more awards than it ever has in its long history—including the Connecticut League of History Organizations Award of Merit and a nomination by Congressman Jim Himes for a national award from the Institute for Museum and Library services. I am humbled to have personally received the New England Museum Association award for excellence in the field and to have been named a Paul Cuffe Memorial Fellow at the Munson Institute of Mystic Seaport this past summer. And, of course, there is the AASLH award we were honored to receive this past Saturday.

The greatest reward that we’ve reaped, however, is not these accolades. It is the environment we’ve built at WHS through support and teamwork of our staff, Board of Directors, and Advisory Council Members.

Beginning in 2014-15 and continuing for the next three years, WHS Board of Directors and Advisory Council participated in a program run by the state of Connecticut for small museums and history organizations. That program, called StEPs, allowed these prominent community members to engage with and examine the operations of the organization and vote for a strategic plan that encompassed sweeping change to bring the museum to the next level. Enacting those changes has been our major focus over the last 24 months and has included everything from the physical space to collections management to programming and the quality of our exhibits.

While all of these stakeholders have been integral to our success—joining meetings and learning sessions every step of the way, there is one group that has been most important of all: You.

The public has been, in many ways, our most important partner in transforming WHS into a place where all feel represented with excellence—with a good dose of fun thrown in, of course!

And so, we say thank you—to all of those who have made WHS what it continues to be—a museum that has been amply rewarded with the privilege of reinvigorating history for everyone.