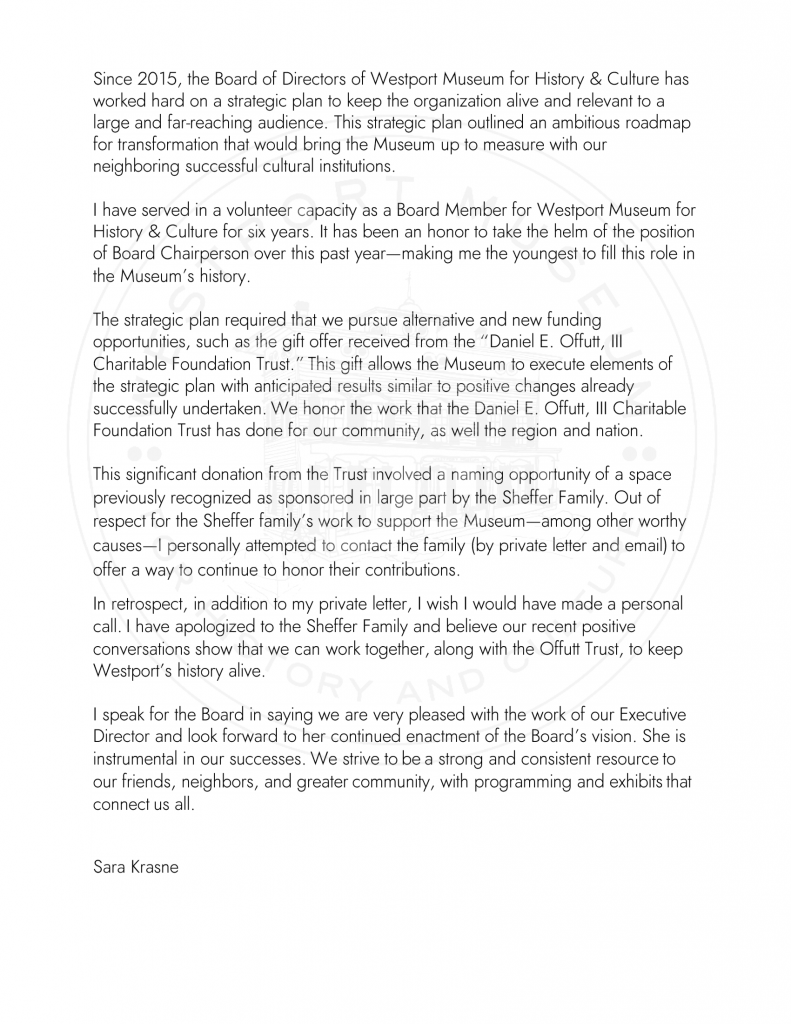

In the evening hours of January 24th, one day before the Lunar (Chinese) New Year, a five-alarm fire ripped through the building housing the archives of the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA NYC) on Mulberry Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown. It took eleven hours for firefighters to control the flames. Thankfully, no lives were lost. While the fire did not reach the precious artifacts housed at the site, the water from the fire hoses did. The damage to the collection which features items from Chinese-American history not found elsewhere is catastrophic. Estimates put the number of lost artifacts, spanning 160 years of history, at 85,000.

As the flames consumed the building and the water came pouring down our hearts were flooded with sorrow for our colleagues at MOCA NYC. After all, a museum’s collection is the museum. Archives such as the ones housed at MOCA—and to a large extent at Westport Museum (WM)—are remarkable for the glimpse they offer into overlooked people whose everyday lives are the real foundation of our collective national story.

When terrible disasters like these strike it’s human nature to take stock of our own affairs. That is true for individuals and for organizations: You ask yourself whether you are doing all you can to prevent the unthinkable.

MOCA NYC thought it had done just that. Following best practices, the museum’s archives and collections were housed on secured, upper floors. On the contrary, Westport Museums’s own archival vault was placed below grade when it was installed decades ago.

Photograph Courtesy New York City Fire Department

This has caused persistent concerns about temperature and humidity control. While 70 Mulberry is a 120 year old building, renovation presumably made it stable enough to withstand the weight of such a large trove of objects and papers. Conversely, WM’s costumes collection weighing many tons was housed in a second floor bedroom of Wheeler house—a 155 year old residential site adapted from a 1795 structure. It was not built to withstand that kind of weight. Worse, the collection sat on top of a load bearing beam that had been flagged as unstable decades previously.

Most agonizing, perhaps, for the MOCA curators and archivists was the fact that their extensive holdings had been professionally, painstakingly cataloged and maintained over years. Sadly, small organizations (ours included) are often handled by dedicated, untrained volunteers who don’t always know or follow best practices of museum collections management.

Today, three years after the Westport Museum’s Board of Directors’ adoption of a strategic plan created as part of the Standards of Excellence Program for History Organization (StEPs) developed by the American Association for State & Local History (AASLH) we are on a steady path to professional management of our holdings.

StEPs “helps history museums, historical societies, historic house museums and libraries with archival collections build professionalism and ensure their programs and collections remain vibrant community resources.”

We’re taking the mandates we learned from StEPs very seriously. But what does that include?

For example, archival storage is a very specific science that includes specialized storage containers, temperature and humidity controls, and precise cataloging for the purpose of research. We are ensuring all of our collections items are housed in the proper boxes, files, cases and cloth.

In the past, our vault was misused as generalized storage (including gift shop inventory) and there was no way to know what was there. There was only a sparse index and few Finding Aids which are necessary and standard in research institutions. Because there was a long list of folks with access to the vault and the building, there were no controls in place to protect our holdings—some of which are priceless (at least to us) in the pursuit of historical research. This may not seem so bad (many people think we should be more “easy going” as a small community institution), but our nonprofit status requires we follow certain protocols to protect collections. To neglect, destroy, improperly dispose or allow mishandling of them is considered an abdication of responsibility and is specifically against the law. Since 2018 access to the vault is no longer unregulated.

Our HVAC and humidity systems have been repaired and upgraded and we are going through an extensive cataloging and digitization process using volunteers and grant funds. Conservative estimates indicate that this will take close to $250,000 to complete. Our goal is to hire professionals to help get things in order–including digitizing our material, with correct finding aids, so that many of them will be available to researchers online free of charge through a program with the Connecticut State Library.

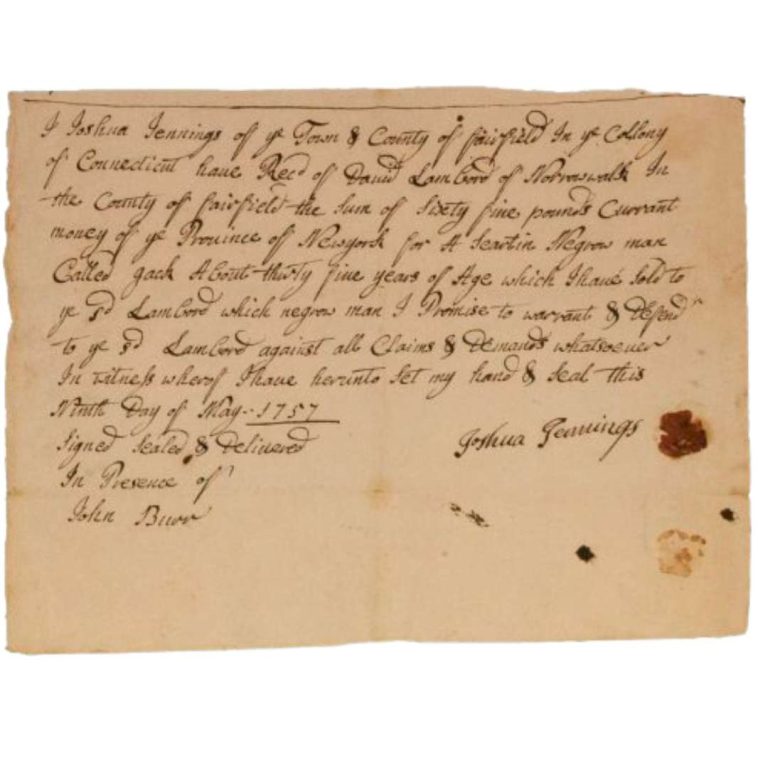

Bill of Sale, 1757, One of the collections held in WM’s vault

When digitization is done we will have to charge image reproduction fees on a sliding scale based on usage (commercial, private, nonprofit.) In the past, WHS copyrights were not always respected but we are trying to remedy this with the fee structure. This is common for institutions like ours. For example: We have been quoted research and usage fees from fellow nonprofits for work on our own behalf anywhere from $150 to $2000 depending on how extensive our request is. When we can afford to make use of these institutions and pay their fees we do so without complaint—because we know the money is going right back into the management of their important collections.

In our vault we have documents dating back 300 years. The work we are doing today is meant to, hopefully, preserve them for 300 more. It’s a long process with as many steps backwards as forwards—the structural failure in our building attests to that. Like other nonprofits, lack of funding exacerbates these challenges but we will persevere with dedication and professionalism.

Even so, no organization is disaster proof. The MOCA NYC’s story proves that. We can only hope to mitigate catastrophe if it strikes with an updated disaster management plan that takes the limitations of our physical space and previous construction into account.

Thankfully, our friends at MOCA NYC have mobilized quickly and are in the process of recovering whatever they can from their damaged collections. We believe it’s our responsibility to stand by our museum colleagues and help whenever we can. Some of our staff have personally donated to MOCA NYC’s fire recovery fund. We are asking our member community to find it in your hearts to perhaps do the same here.