The establishment of the Congregational Church of America dates back to the founding of this nation with the arrival of religious dissenters from England to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1620. Called Puritans in England — a derogatory term referring to their zeal for simplicity in church organization and worship — they believed each church should be organized with members who enter a covenant agreement and had the right to choose their own minister.

In the 1630s and 1640s, thousands of Puritans arrived in New England and flourished with the conviction that they were chosen by God to play a central role in the unfolding of this new land and human history at large. As such, churches and church leaders played an important role in shaping New England society. The organizational system of Congregational churches required mutual trust and personal commitment, yet this was not always a given. Voting in Massachusetts was limited to individuals who had been formally admitted to the church after a detailed interrogation of their religious views and experiences. Thomas Hooker disagreed with the limitation of suffrage in the Massachusetts Colony and in 1636, led one hundred followers to found Hartford. After 1636, freeman (eligible voter) settlements were formed throughout Connecticut.

In 1639, Roger Ludlowe and a group of settlers from Windsor came to modern day Fairfield and formed The First Church of Fairfield. By 1644, Fairfield was the fourth largest town among the colony’s nine towns and extended from Stratford to Norwalk. As populations grew and church attendance was mandatory, groups began campaigning for the right to establish their own parishes. In 1708, the Bankside farmers, Thomas Newton, John Green, Henry Gray, Daniel Frost and Francis Andrews started their petition to form the West Parish of Fairfield, which is the modern day Green’s Farm Church in Westport.

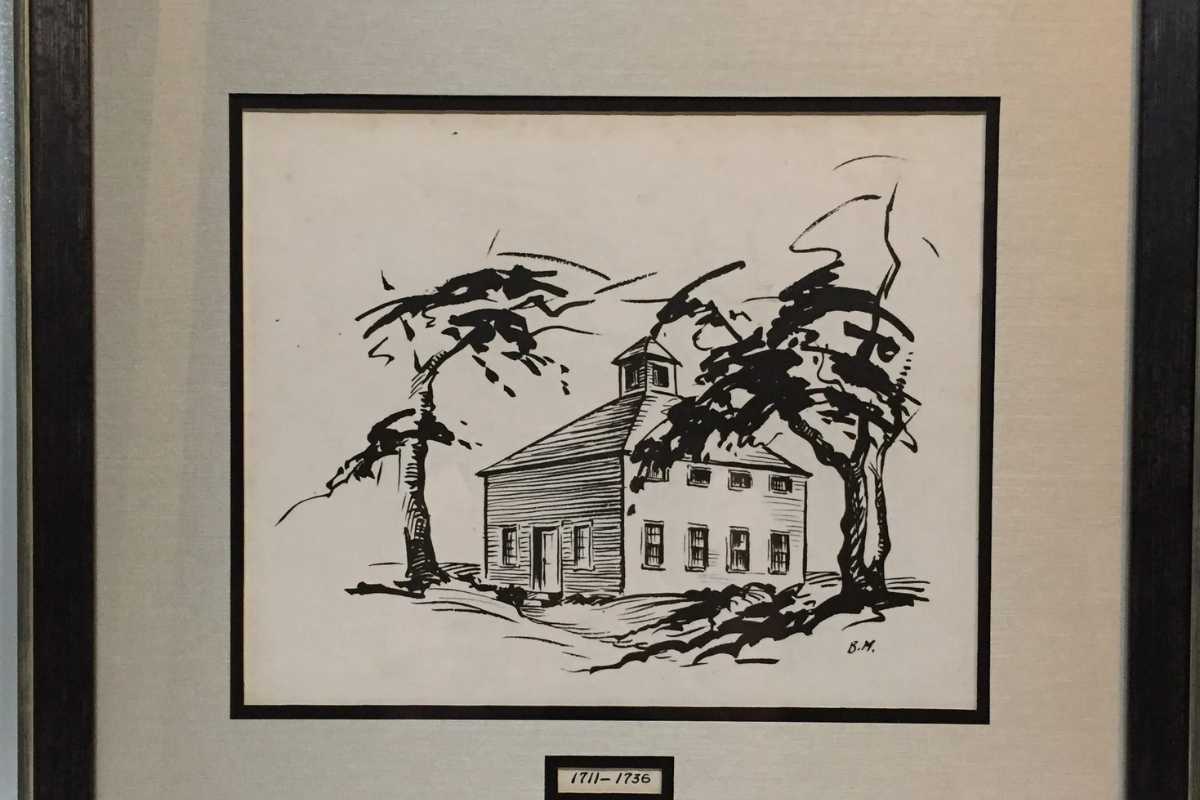

Green’s Farms Church, 1711 – 1736

Rendering by unknown artist

Loan from Green’s Farms Church

In 1708, a group of Fairfield residents commonly known as the Bankside farmers petitioned the Connecticut Colonial Legislature for permission to leave Fairfield Parish. They wanted to establish a parish closer to their homes in the area between the current Weston center to the north, Long Island Sound as the southern border, the Saugatuck River to the west, and today’s West Parish Road as the eastern boundary. After a three-year debate ensued, the Legislature granted their request in 1711.

The first parish meeting was held on June 12, 1711, and Reverend Daniel Chapman was chosen as minister, with the promise of 70 pounds annual salary and one year’s worth of firewood. The modest meetinghouse, pictured here, took nine years to build and was 35 square feet wide and 16 feet high, with 4 ½ foot wide clapboard siding. It stood on the common at Green’s Farms Road and Morningside Drive, commemorated today by the Machamux boulder.

Tea Bowl and Saucer, c. 1720

Ceramic

Loan from Green’s Farms Church

This tea bowl and saucer belonged to Reverend Daniel Chapman, the first minister of Green’s Farms Church. The congregation paid for Chapman’s ordination in 1714, and he served the West Parish of Fairfield for 31 years. Porcelain was costly in the 18th century and common folks used pewter or even wood vessels. Reverend Chapman, in contrast, likely had a full set as evidenced by the five remaining pieces the church still owns.

Tea was also an expensive 18th century indulgence. The fact that Reverend Chapman owned a full set indicates he was highly valued and lived in refined style. The earliest tea cups had no handles and were referred to as tea bowls. In the 18th century, saucers were typically very deep compared to modern day saucers. It is believed that tea was poured from the bowl to the saucer to cool and was then drunk from the saucer.

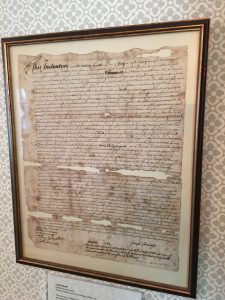

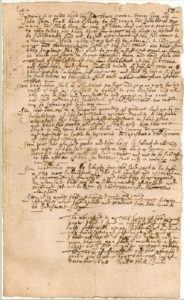

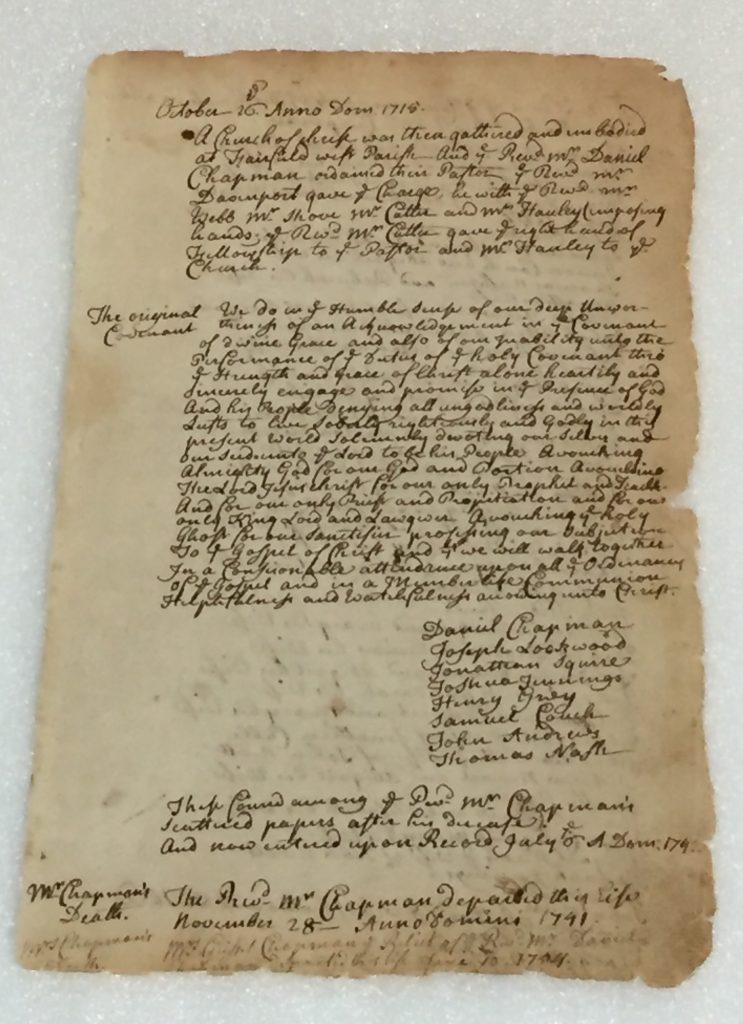

Green’s Farms Church Covenant, 1742

Rewritten Copy of 1711 Document

Courtesy of Fairfield Museum and History Center

As they formed a new congregation in 1711, one of the first orders of business for the Bankside farmers was to create a covenant of faith. The covenant outlined the expectations of the congregation…”Denying all ungodliness and worldly Lusts, to live Soberly, righteously and Godly in this present world.” It was signed by the original settlers of Green’s Farms: Joseph Lockwood, Jonathan Squire, Joshua Jennings, Henry Gray, Samuel Couch, John Andrews, and Thomas Nash who later became known as the Bankside Farmers.