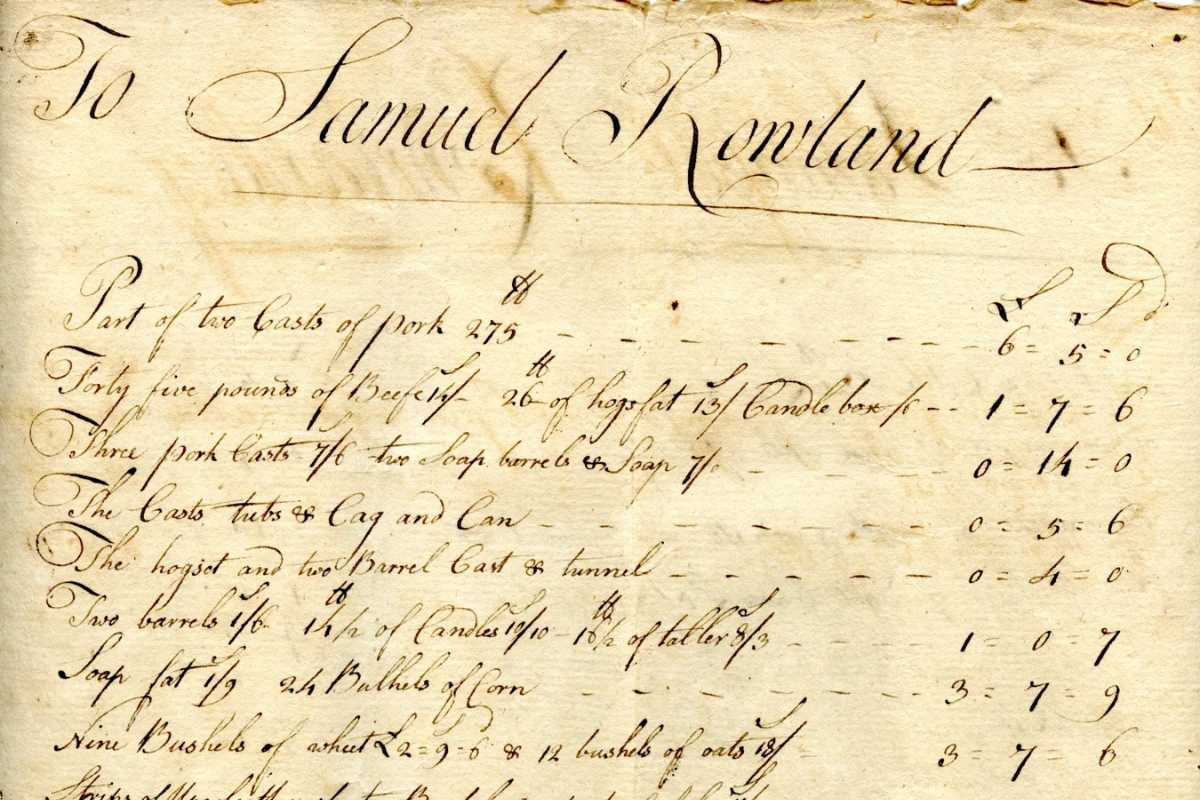

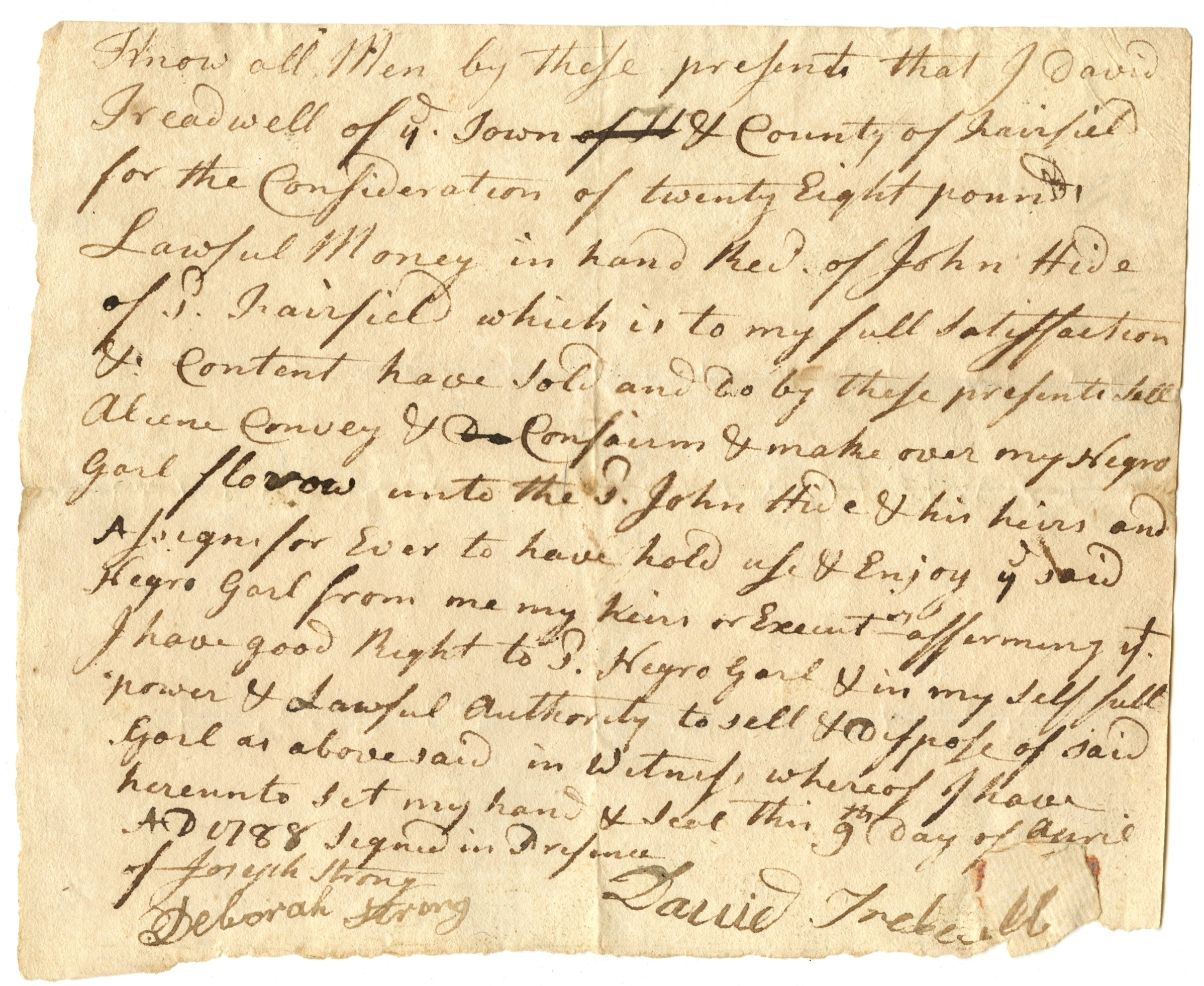

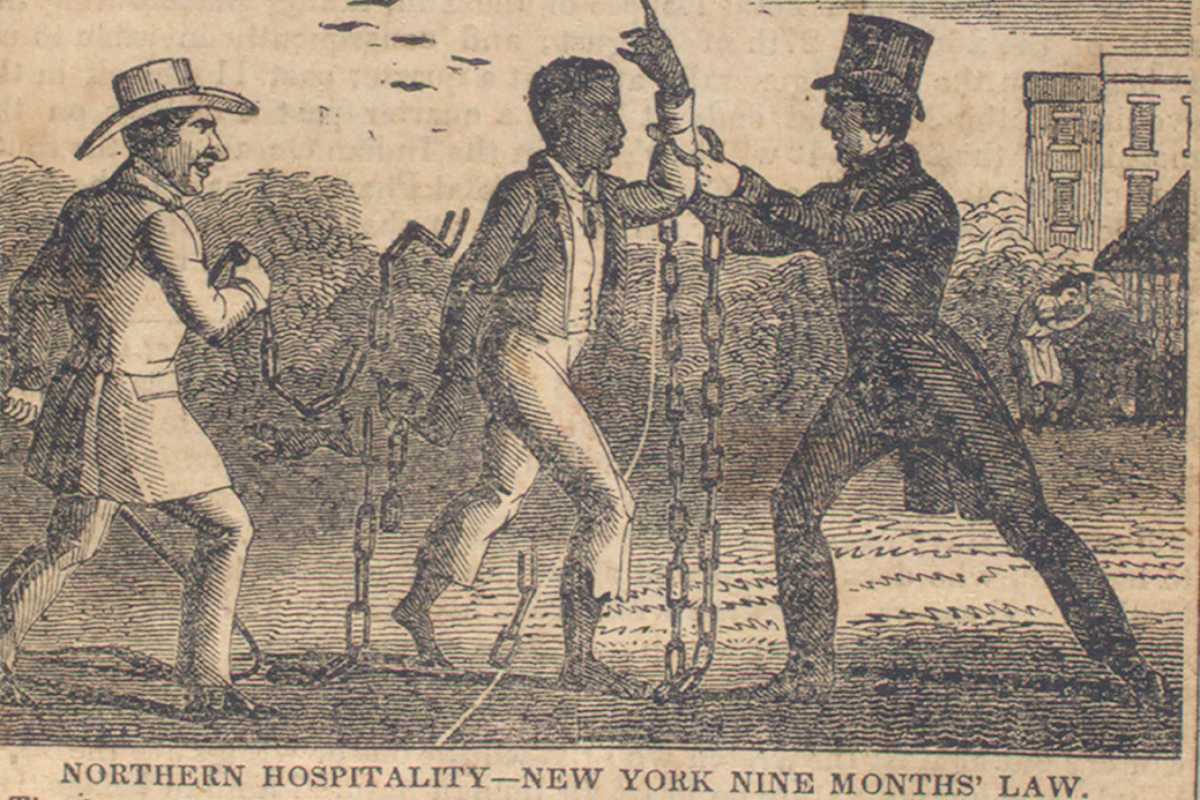

The commonly held belief that slavery didn’t exist in New England as it did in the American South is a myth. Texts from Hartford and New Haven in 1639 and 1644, respectively, refer to enslaved African people in Bristol. By the 18th century Newport, Rhode Island and New London, Connecticut surpassed Boston as major slave trading ports.

Slave trading was a key facet of the Triangular Trade between Africa, the Caribbean, and New England. Just before the American Revolution, most of New England’s trade was with sister colonies in the British West Indies (the Caribbean). New England farms sent wood, livestock, and food to sugar plantations in the Caribbean that were so focused on sugar production, that not an acre of spare land was given over to other crops. In return, northern colonies received sugar, rum, molasses, and enslaved people who originally hailed from Africa. Manufactured goods were also sent directly to Africa from New England to barter for enslaved people.

The entire Triangular Trade economy was completely dependent on the work of enslaved Africans. In New England, enslaved people worked farms that produced food exports for the West Indies largely to be consumed by the many thousands of enslaved people working sugar plantations.The Caribbean was so dependent on North American exports that famine swept the islands during the American Revolution when British blockades prevented the arrival of American trading ships. In Jamaica alone, thousands of enslaved people died of hunger.

In Connecticut, river ports like Middletown did brisk business on the Triangle Trade. New England slave traders grew quite wealthy. In Boston, Peter Faneuil built a public meeting house, Faneuil Hall, with his inheritance from his slave-trading uncle’s estate. Faneuil Hall is often called the “Cradle of Liberty” for its role as a meeting place for American Revolutionaries.

While most enslaved people arrived on American shores via the Caribbean, the ship Africa brought enslaved people directly to New London from West Africa. The 1798 book, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa by Venture Smith, gives a first-hand account of the horror of the trip from Africa to Newport on a ship that was likely The Charming Susannah. In Newport, Smith was traded for “Four gallons of rum and piece of calico cloth.”