African Americans have served the American military with distinction, even in the time when they themselves were not free. In the Revolutionary War, many of the African American men from this community joined the ranks of soldiers on both sides.

At first African Americans were barred from enlistment in the Continental Army, while the British admitted them into the ranks. Some African Americans hoped for freedom in return for service, others threw in their lot with the British regulars. Often, patriots who did not want to fight sent their enslaved people to fight in their stead or to work for the Continental Army in some capacity including as spies and double agents like enslaved Virginian, James Armistead Lafyette, who served under the Marquis de Lafayette.

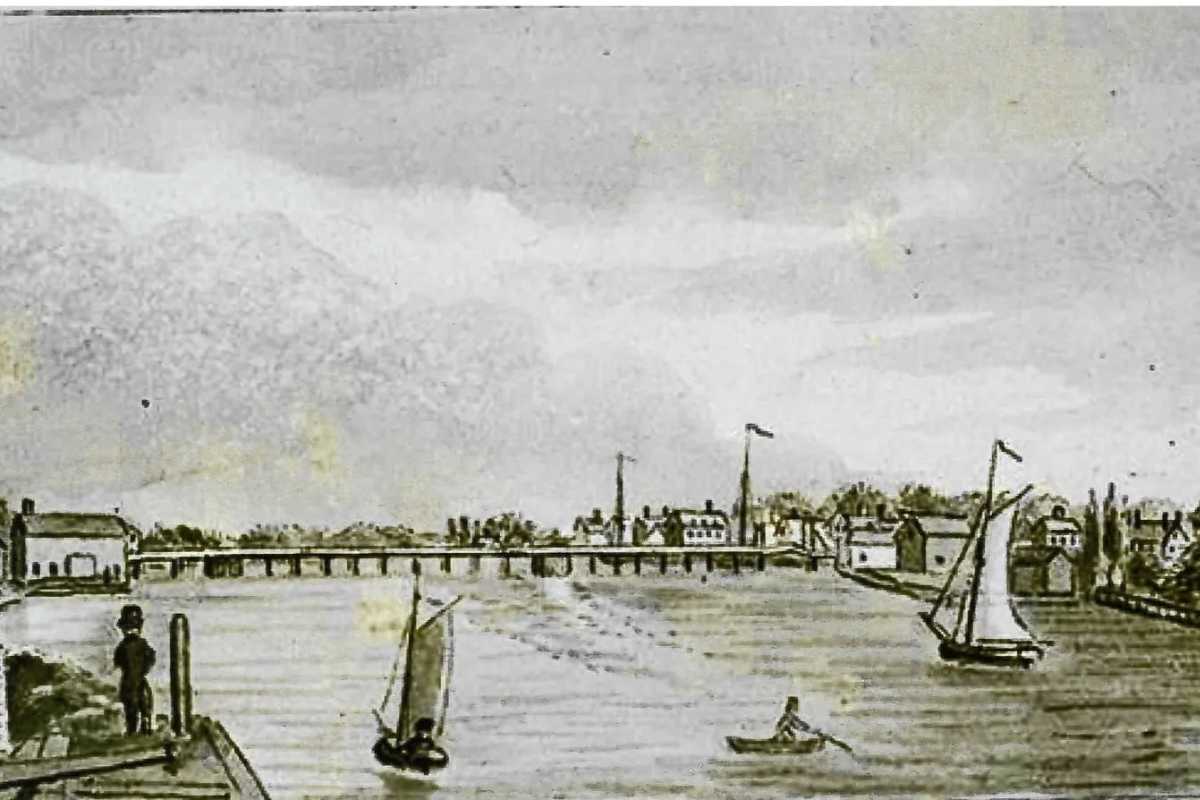

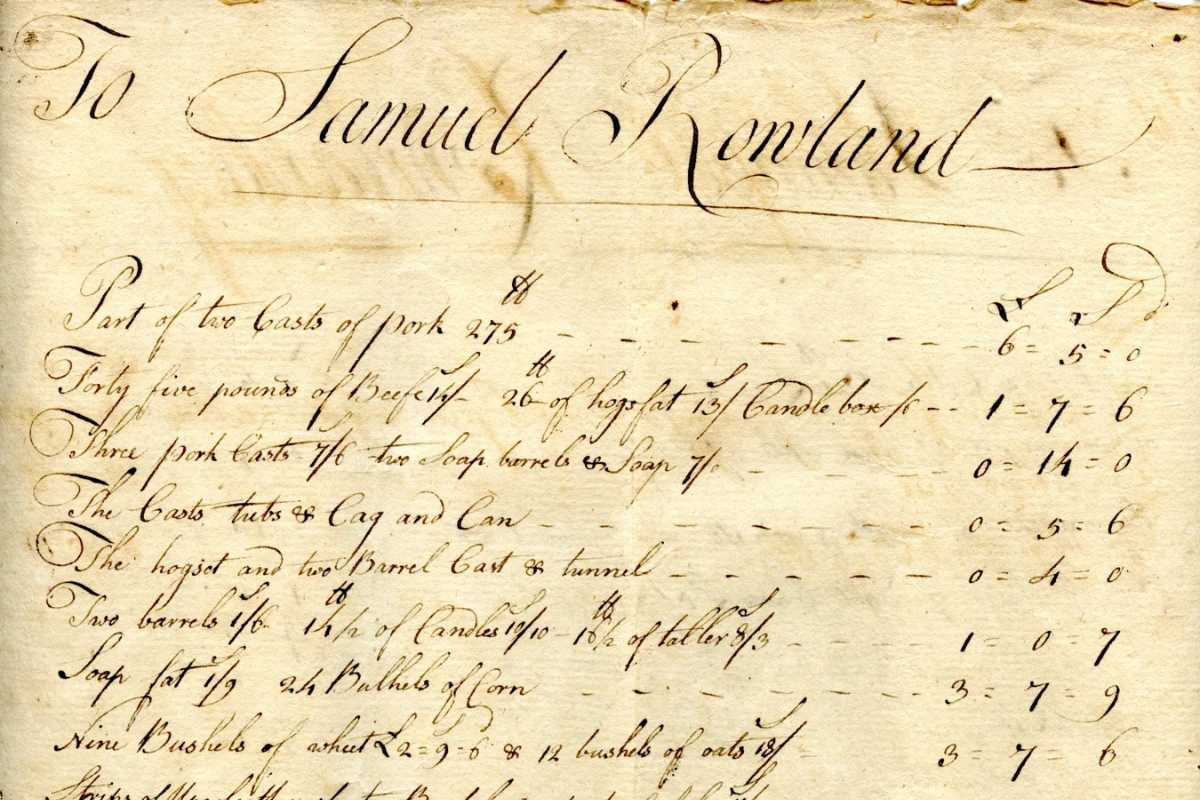

Jack Rowland of Fairfield earned his emancipation in return for his service in the Colonel Bradley’s Connecticut regiment, serving at the battles of Ridgefield and Germantown. Cato Treadwell also of Fairfield joined as a free man in New York. Both soldiers petitioned Congress to receive their pension for time served in the War for Independence. Their counterparts Ishmael Coley, enslaved by Ebenezer Coley of Westport and Tom Hide, enslaved by John Hide of Westport both escaped to enlist with British forces, departing with them at the war’s end.

African American soldiers from Westport and Connecticut at large served on both land and sea in all the wars that followed, usually in segregated units. This was despite the fact that The First Rhode Island regiment accepted black soldiers in 1778 following poor enlistment among able-bodied white men. It was the first integrated regiment in American history.