Back in 2018, Westport Museum (then Westport Historical Society) did a year-long exhibit called “History of Westport in 100 Objects” in which we shared the nearly four hundred year history of the town using different objects. We are bringing back that always-popular exhibit here–virtually. Check back each week for a new post and photos of items that tell our collective story. Have a suggestion for an object to include? Email us a photo and description at virtualmuseum@westporthistory.org and we’ll consider including it on our facebook page.

There was no “Westport” in the 1630s. Instead, using the Saugatuck River as the boundary, the town was divided between Fairfield and Norwalk. On the Fairfield side, many farmers settled along the Long Island Sound–amidst the original settlements of the Paugusset Natives who were “cousins” and allies of the larger, more powerful Pequot tribe.

By 1637, there was all out “war” between the two groups. Originating in Massachusetts, Europeans hounded the Pequots all the way to the swampy area between what is now Southport and Greens Farms. The massacre that ensued was called the Great Swamp Fight and effectively ended the war and the Native presence in this part of the colony.

The Native People who survived were either absorbed by other tribes or sold into slavery. Over the years, their presence has been erased except for the now familiar place names they left behind like Saugatuck and Aspetuck.

Powderhorn, 19th Century

Unknown Artist

Animal horn and wood

WHS Collection, Unnumbered

Animal horns were commonly used throughout the Colonial period of Connecticut to hold gunpowder. Horns from cattle or oxen were readily available and popular with militiamen before the adoption of paper cartridges. Susceptible to sparks and explosions, metal receptacles could not be used to hold powder but other containers, known as powder flasks, crafted from leather or wood, were employed. The powderhorn seen here would have been refilled through the large opening, with powder poured through the tapering end for each shot, and worn slung over the shoulder from a leather strap. Powderhorns were used both by hunters and the militiamen raised under orders of the Colonial Governor to engage Native People in battles for territory. A powderhorn such as this one would have likely been used by colonists during battles like the Great Swamp Fight at the border of present day Greens Farms and Southport.

Arrowheads, 12oo BC-950 AD

Unknown Native People

Quartz and Quartzite

WHS Collection, 1978.11.5 (1-5)

Arrowheads found in Connecticut date back as early as 1,400 years ago as seen at the Tower Hill Road Site in the southeastern part of the state. Many of the arrowheads over this timespan were made from quartz and quartzite, and their designs varied. The Mohegan, Pequot, Pocumtuc, and Narragansett people were based in southern New England for thousands of years. Native People hunted wild game and fought tribal wars using arrows outfitted with these sharp stone heads. As white settlers arrived, conflicts ensued such as the King Philip’s and Pequot Wars including the Great Swamp Fight just past today’s Green’s Farms on the border of Southport. While white settlers used guns, Native Peoples attempted to protect their land using bow and arrow. Arrowheads found today help historians track the paths of these conflicts.

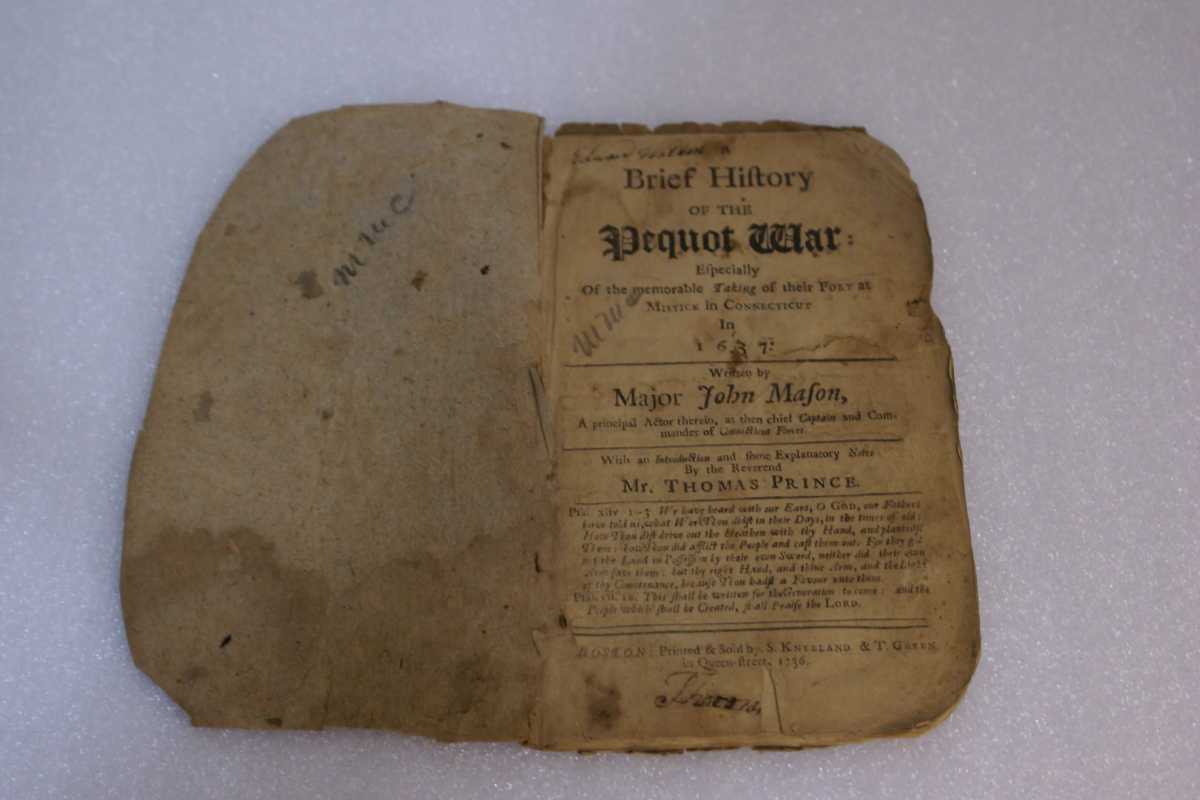

A First Hand Account of the Pequot War, 1637 (published 1736)

Major John Mason

Book, stitched parchment in custom board/leather binding box

WHS Collection, 30073

On July 13, 1637, Major John Mason, Captain and Commander of the Connecticut forces, brought his men to battle with Native People during the Pequot War in swampy land in what is today Southport in the area where I-95 crosses over the Post Road. This is an original surviving copy of that account first published in 1736. Pages 15-18 describe the Swamp Fight. Mason’s militia men comprised local farmers. The Sachem of the Pequot, Sassacus, was captured along with some 180 men, women, and children of the Pequot tribe–making this the last official battle of the war. You can see a monument dedicated to the battle in the center divider at the intersection of Post Road and Old Post Road near the Athena Diner in Southport today.

“We then Marching on in a silent Manner, the Indians that remained fell all into the Rear, who formerly kept the Van; (being possessed with great Fear) we continued our March till about one Hour in the Night: and coming to a little Swamp between two Hills, there we pitched our little Camp.”

Pequot War Mural, 1937

Scan of Original Painting

Courtesy of Fairfield Museum and History Center

Depictions such as this Great Depression era mural by artist George Avison told a romanticized—if inaccurate—story about the Great Swamp Fight. Similar to other art commissioned by the Works Progress Administration to glorify the era of American nation building, this mural was one in a series of five murals depicting Fairfield’s history. Completed in 1937 and hung in the Roger Ludlowe High School building, now known as Tomlinson Middle School, where all five remain today as a reminder that history is most often told through the eyes of the “victors.”

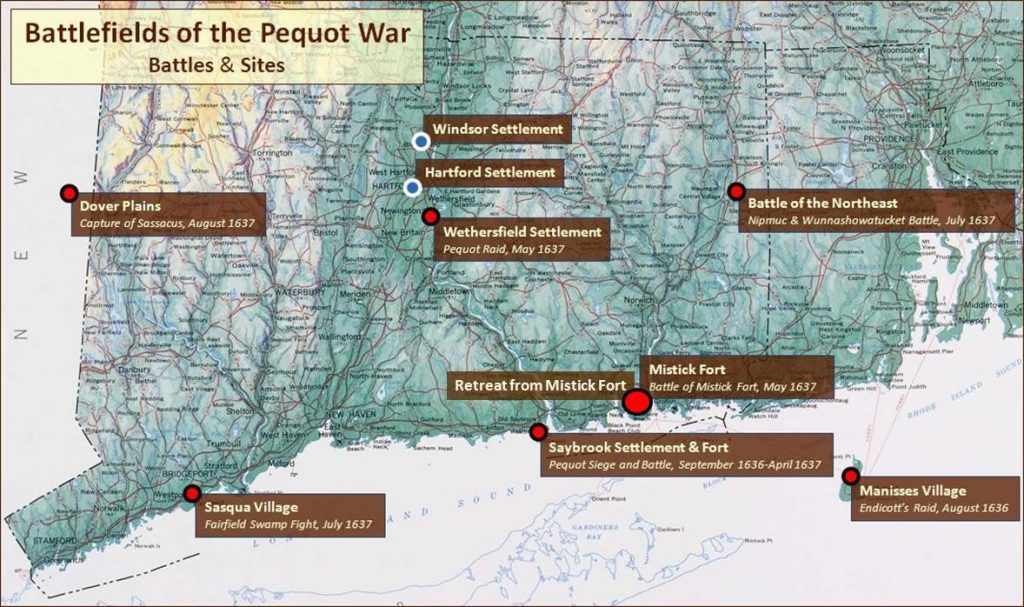

Battlefields of the Pequot War

Courtesy of Fairfield Museum and History Center Pequot War Battlefield Project

This map created by the Fairfield Museum and History Center as part of a multi-year collaboration with the National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program shows the locations of the Connecticut battle areas in the Pequot War. The Southport site has been mapped topographically to create a site plan for professional archaeologists to conduct low-impact field analysis of the Pequot Swamp battle site to locate possible artifacts. To learn more, please visit the Pequot War Battlefield Project at fairfieldhistory.org